From the April 1965 issue of Car and Driver.

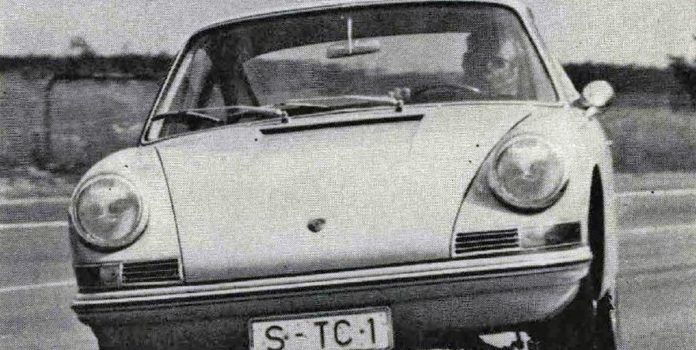

No contest. This is the Porsche to end all Porsches—or, rather, to start a whole new generation of Porsches. Porsche’s new 911 model is unquestionably the finest Porsche ever built. More than that, it’s one of the best Gran Turismo cars in the world, certainly among the top three or four.

Porsche enthusiasts used to insist that the 356 model was as nearly-perfect an automobile as had ever been designed, an immutable classic that couldn’t be improved upon. Oh, no? Put a familiar 356 up alongside a 911. Only yesterday, the 356 seemed ahead of its time. Today you realize its time has passed; the 356 leaves you utterly unimpressed and you can’t keep your eyes off the 911. The 911 is a superior car in every respect…the stuff legends are made of.

Let it be understood at the outset that the 911 does not replace the 356, according to the factory. In the catalog, it replaces the fussy, little-appreciated Carrera 2 while the 356C (ex-Super) and 356SC (ex-Super 95) still roll off the assembly lines at about their normal rate. However, we can’t believe that Porsche will continue making two entirely different cars, side-by-side, beyond the immediately foreseeable future. And let it also be understood that the 911 is not readily available. The first six month’s production is completely sold out and there’s a line of expectant owners going halfway around almost every Porsche agency in the country.

Overview

The 911—so-called because it is the 911th design project since Porsche opened its doors in 1931—is also the first all-Porsche Porsche. The 356 was the first car to carry the Porsche name, although when it was conceived in 1948 it was little more than a souped-up, special-bodied version of an earlier Porsche design, the Volkswagen. The 911, while true to the 356’s basic configuration, is an entirely new and different car. The engine is again air-cooled, again hung out behind the rear axle, but it’s a single-overhead-cam six-cylinder whereas the 356 was a pushrod four-cylinder (and the Carrera a four-cam four-cylinder). The new body is far more handsome—the work of old Professor Porsche’s grandson, Ferry, Jr. The 9ll’s 5-speed gearbox, already in service in Porsche’s 904 GT racing car, is probably the new car’s best single feature. Even the suspension is new, though tried-and-true torsion bars are retained as the springing medium.

The 911, or 901 as it then was, was introduced at the 1963 Frankfurt Auto Show. It was very much a prototype and its debut may have been premature. More than a year was to pass before it went into production, during which time the model number was changed (to indicate that it was a later model than the Frankfurt car and also because Peugeot reportedly had a lock on three-digit model numbers with zero in the middle), the price estimate dropped, the performance estimate rose, and a demand built up that the current four-a-day supply won’t be able to satisfy for some time to come.

The 901/911 was not the “best” car Porsche could have made. Porsche could have put the storied flat-eight engine into production, bored out to, say, 2.5 liters and tuned up to 240 horsepower. That would have put the 901/911 into the Ferrari-Corvette-Jaguar performance bracket. It also would have raised the price considerably, and Porsche was understandably nervous about entering the No-Man’s-Land market for $9000 GT cars. On price alone, it would have been beyond the reach of anybody but the Very Rich, and the V.R. are noted for such capricious perversity as preferring a $14,000 car to a $9000 car simply because it costs $5000 more. The four-cam flat-eight also would have had the same kind of maintenance and reliability problems the Carrera engine had; problems that are hopefully nonexistent in the 9ll’s SOHC six-cylinder.

Considering what the Stuttgart design office has turned out in the past, Porsche could have come out with a supercharged six-liter 550-hp V-16 GT car to sell for $30,000 and not lose a drag race to anybody but Don Garlits, but their production facilities are hardly geared for that sort of thing, and it would be getting pretty far away from the Porsche image, wouldn’t it? In fact, Porsche had a full four-seater on the drawing boards at one point, but Ferry Porsche felt that his company’s business was not selling super-duper sedans or ultra-ultra sports/racing cars but optimum-priced, optimum-size, optimum-performance Gran Turismo cars, which is exactly what the 911 is.

At $6490 POE East Coast (or $5275 FOB Stuttgart), the 911 isn’t what you’d call cheap—no Porsche ever was—but then, quality never is. Porsche’s kind of quality cannot be had for less, viz. Ferrari 330GT ($14,000) or Mercedes-Benz 230SL ($8000). It’s of more than ordinary interest that the 911 costs a whopping thousand dollars less than the Carrera 2 it replaces. A Porsche is either worth it to the prospective buyer or it isn’t; he can’t justify the price tag by the way the body tucks under at the rear or by the way the steering wheel fits in his hands or the way the engine settles in for a drive through a rain-filled afternoon. But let’s see what he gets for his money.

Body

The 9ll’s eye-catching body is distinctive—slimmer, trimmer, yet obviously Porsche. While not as revolutionary as the original 356 design was in its day, the 9ll’s shape is far less controversial and slightly more aerodynamic. Though the frontal area has grown, a lower drag coefficient (0.38 vs 0.398) allows it to reach a top speed of 130 mph with only 148 hp. It ought to weather the years without looking dated. Compared to the current 356 body, the 911 is five inches longer (on a four-inch longer wheelbase), three inches narrower (on a one-inch wider track), and just about the same height. The body structure is still unitized, built up of innumerable, complicated steel stampings welded together (with the exception of the front fenders which are now bolted on for easier repair of minor accidents). The glass area and luggage space have been increased by 58 percent and 186 percent respectively, and the turning circle is a bit tighter. The fully trimmed (with cocoa mats) trunk will hold enough for a week’s vacation for two; additional space is available in the rear seat area. The trunk and engine lids can be opened to any angle and held by counter-springs and telescopic dampers—a nice touch. These lids, as well as the doors, are larger than the old Porsche’s, making access to the innards much less awkward. The gas filler cap nestles under a trap door in the left fender, and the engine lid release is hidden away in the left door post.

The generous expanse of glass area does wonders for rearward vision; all-around visibility is comparable to a normal front-engined car. The bumpers are well-integrated with the body, though provide barely adequate protection from those who park by ear. The standard appointments are lush and extensive: two heater/defrosters, padded sunvisors with vanity mirror, map and courtesy lights, 3-speed windshield wipers, 4-nozzle windshield washers, chrome wheels, belted tires, two fog lamps, a back-up light, and a beautiful wood-rim steering wheel. About the only options we’d like are seat belts (for which massive, forged eye bolts are provided), a radio, and a fender mirror. Fitted luggage and factory-installed air-conditioning will be available shortly, we’re told.

Interior

The ads tell you a Porsche is “fun” to drive. Fun? A Mini-Minor is fun to drive because it can’t be serious; everything about it is incongruous—it defies all known laws of nature…and marketing…and gets away with it. The Porsche—any Porsche—is no fun at all; Germans aren’t much given to frivolity. Porsches are designed by drivers, for drivers, to be driven very matter-of-factly from Point A to Point B in maximum comfort, speed, and safety. Form soberly follows function, and the cockpit of a Porsche is laid out to achieve just that end. The controls and instruments are efficiently positioned, and this economy of effort and motion is why Porsches aren’t tiring to drive. But fun? Porsches are for driving.

As befits a driver’s car, the controls are superb. The steering wheel is a special joy; the shallow “X” of the black anodized spokes provides perfect thumbrests without obscuring any of the unusually comprehensive instrumentation. The reach to the wheel is just right, and all the secondary controls are operated by stalks on either side of the wheel. The driver can signal for turns; flash, raise, and dip the headlights; and operate the windshield wipers and washers, all without moving his hands from the wheel. The gearshift lever has less travel than the 356’s, is smoother, and requires no more effort. The pedals are beautifully positioned for long-distance touring or fancy heel-and-toe footwork; there’s even room to rest the left foot between the clutch and the front wheel arch.

The seats have the wondrously-comfortable Reutter reclining mechanisms, and are softly sprung and upholstered in cloth with leather edges. They will adjust to fit anybody under seven feet and 300 pounds. Head-and hip-room are similarly commodious; shoulder room is about the same as in the 356. The rear seats are a different matter. Though the 911 is occasionally described as a 2+2, the space back there is very cramped. It can hold an adult-sitting sideways with head bent forward—or a child, but neither for very long. It is more properly a luggage area, and for that purpose, the seat backs fold down to form a shelf for a couple of fair-sized suitcases.

The dashboard is a magnificent edifice. The instrumentation is complete even to an oil level gauge (no messy mucking about with a dipstick for the 911 owner). Directly in front of the driver is a huge, 270° electrical tachometer. To its left are gauges for oil and fuel levels, oil pressure and temperatures, and sundry warning lights. On the right are a speedometer, odometer, a clock, and a few more colorfully flashing lights. About the only thing we didn’t like about the dash was the strip of teak running full-width below the instruments. The Porsche people are extremely proud of it, it’s supposed to look elegant. It looks as if someone said, “Let’s put a strip of teak here; it’ll look elegant.” It doesn’t. If we owned a 911 (dare we dream…?), we’d paint it flat black to match the rest of the leatherette-covered dash.

The normal heater, which draws heat from the engine, is supplemented by a gasoline-powered device hidden away under the floor of the trunk compartment. The normal heater, controlled by a small lever just forward of the gearshift, has outlets ahead of each door (which can be closed—or adjusted—by sliding covers), at the base of the windshield, and at the rear window. The auxiliary heater, primarily a defroster, draws air from a grille behind the front seats and provides instant heat. It exudes a faint odor of gasoline but is only used in slow traffic or until the engine warms up. A variable-speed fan circulates air from either heater.

Draft-free ventilation with the windows rolled up is possible at any time of year; fresh air is picked up from the high-pressure area ahead of the windshield, controlled by a lever on the dash, and exhausted through the headliner material and out nearly-invisible slots just above the rear window.

The handbrake is between the front seats, whence it migrated from under the 356’s dash. The doors and dash abound with armrests, grab handles, door pulls, push-button door openers and locks, map pockets, a cigarette lighter, an ashtray, and a lockable glove box.

Engine Details

The 911’s engine is Porsche’s first attempt at a six-cylinder; the two extra cylinders were added for smoother, less-highly-stressed operation. The prototype we drove at the factory had twin exhausts and sounded uncomfortably like a Corvair. The production cars have a single exhaust and a sound all their own. It’s rated at 148 SAE horsepower.

The engine idles somewhat uncertainly at 800 rpm but is smooth as a turbine from 1000 rpm on up to the 6800 rpm redline. It revs quickly and freely, like a competition engine with a light flywheel. Around town, the 911 can be driven in first and third (up to 93 mph) alone; on the highway, it will pull from 2000 rpm in fifth. Sixty mph is less than 3000 rpm (100 mph is only 4900 rpm), making turnpike cruising relatively quiet and effortless on the engine.

During the 911’s gestation period, a lot of attention was given to the carburetion, but it still isn’t perfect. The 911 has six individual single-throat Solex PIs, “floatless” carburetors in which the fuel level is maintained in a separate reservoir and recirculated by a second fuel pump (mechanical, like the primary pump). All this is supposed to eliminate flat spots, hesitation, and the like. Not quite—they’re still sorting it out in Stuttgart. After meticulous adjustment by Wolfgang Rietzel, Porsche of America’s service representative, one of our otherwise-stock test cars clocked 0–60 mph in 6.8 seconds—substantially better than the average 911 fresh off the showroom floor. Hopefully, the problem will be solved in Germany and not require tedious fine-tuning at local Porsche agencies. On the plus side, the new Solexes are injection-like in their freedom from variations due to lateral or vertical accelerations.

The crankcase is composed of two light-alloy castings bolted together on the crank centerline. The crank itself is a beautifully counterweighted forging running in eight main bearings (the “usual” seven plus one outboard of the accessory drive gears), the first time Porsche has put a main bearing on either side of each rod journal.

The distributor, fan, valve train, alternator, and oil pumps are driven from the rear of the crankshaft. Dry sump lubrication (a la Carrera) is employed, with two whole gallons of oil circulated, by a scavenger and a pressure pump, through a thermostatically-controlled oil cooler and full-flow filter. The overhead valves are driven by a pair of chains (one per cylinder bank; each tensioned hydraulically) via short rocker arms. The rockers allow the valves to be disposed at an angle to each other rather than in-line.

Six individual cylinder heads are clamped between the cylinder barrels and camshaft housings. The fully-machined combustion chambers are hemispherical with fairly large valves (1.54-inch intake, 1.50 inch exhaust). The ports look restricted for 333 cc displacement per cylinder, the valve timing and lifts are conservative and the compression ratio is only 9: 1, indicating that Porsche is holding quite a bit in reserve. We would estimate that 180 horsepower is within reach, either by the factory for a super street machine or by individuals for amateur racing in the SCCA’s class D Production. The upper limit for GT racing, either in a lightweight 911 or the six-cylinder versions of the 904 must be in excess of 200 horses.

The barrels have alloy cooling fins and shrunk-in “Biral” (a special cast iron) liners. The bore and stroke, at 3.15 x 2.60 inches (80 x 66 mm) are fashionably oversquare, with a ratio of .825 (vs. .895 for the pushrod engines and .804 for the 2.0 liter four-cam engine). The pistons are sharply domed with healthy valve recesses.

The axial fan is fiberglass, surrounds the alternator, and is driven from the crank by a V-belt. Single ignition is used in conjunction with 12-volt electrics, replacing the old 6-volt system. Porsche has indicated its confidence in the new engine by extending the warranty from six months/6000 miles to a full year and/or 10,000 miles.

Transmission and Clutch

As mentioned, the five-speed, all-synchro gearbox is the 911’s best single feature. Actually, the torque and flexibility of this engine are such that a three-speed would suffice, but it was Porsche’s aim to be much more than merely sufficient. There is, in effect, a gear for every occasion: one for starting, one for cruising, and three for passing. It is to Porsche’s everlasting credit that it didn’t make first gear superfluous by having second an alternative starting gear—you must start in first, and it’s a pretty long gear at that. In fact, 6800 rpm through the gears gives 44, 65, 93, 118, and 138 mph. All the gears are indirect, with the famous—and flawless—Porsche servo-ring synchromesh. Fourth and fifth gear are actually overdrives, but pulling power is not lost as the upper three ratios are close in an already close-ratio gearbox.

Operating the shift lever is confusing at first. First gear is to the left and back, with the other four gears in the normal H-pattern. Reverse is to the left and forward, but to go from first to second, you just push forward—toward reverse—not forward and right. You half expect it to go into reverse, but it won’t—scout’s honor. Everything else is a piece of cake (the linkage is not as remote as other Porsches’), including changing down to first gear for those mountain-pass hairpins.

Clutch diameter is up to 8.5 inches, and the mechanism should prove more robust than older Porsche clutches.

Steering, Suspension, and Brakes

Porsche is also trying rack-and-pinion steering in a production car for the first time on the 911. It’s fast, precise, incredibly direct, and—like the carburetion—a little late in being perfected. The prototype we drove was subject to torque steer, i.e., changing the throttle position would change the car’s direction. This had been eliminated on the production car, but a new bug had cropped up: The steering felt too direct, like a racing Ferrari—you could feel every ripple in the road. Revised front-end parts are coming through on the latest cars, but it’s almost impossible to make a rack-and-pinion system completely free of kickback. Doubtless, Porsche will work out an honorable compromise between damping action and road feel that will satisfy most customers. Incidentally, the steering column contains two U-joints, not to clear any obstacle (the steering box is on the car’s centerline), but so that it will collapse toward the dash in case of a crash, a good safety measure.

The 911’s suspension is a departure for Porsche. A damper strut system is used at the front with longitudinal torsion bars. This layout takes much less trunk space than the transverse bars of the 356. It also improves control and reduces roll (by raising the front roll center), and has the odd effect of banking the wheels into a turn, like a motorcycle rider. To avoid oversteer, a link-type rear suspension with semi-trailing arms (and transverse torsion bars) was adopted. There is very little camber change on jounce and rebound, so the cornering power is not as variable on an undulating surface as the 356. Koni telescopic shocks are fitted all around, but no “camber compensator” is used, as the new suspension makes it unnecessary. Body roll is moderate, pitch and harshness seem well under control, and the ride is surprisingly soft. In all, it’s a great improvement over the 356 suspension.

The 911 uses 15-inch wheels. A 14-inch wheel would be more aesthetically pleasing (and add to the available interior room) but would have restricted brake size, so we’re not complaining. We will complain about the wheel width, however. The rims are only 4.5 inches wide—what’s happened to all that racing experience? Porsche does have 5.0 x 15 and 5.5 x 15 wheels (from the 904) that will fit; substituting these wheels would yield greater cornering power (and less tire wear) at the penalty of a slightly stiffer ride. We recommend them, and also the ZF-made, U.S.-design limited-slip differential—if you can get them.

The brakes are virtually the same as the four-wheel discs of the 356C. In the 1965 Car and Driver Yearbook we said: “There’s nothing like four-wheel discs…that halfway business with discs at the front and drums at the rear doesn’t even come close. In an emergency, good brakes are probably the single most important factor in avoiding an accident.” The Porsche’s brakes are without peer; smooth, positive, unaffected by water, and absolutely fade-free.

Performance

The performance figures on the specifications page speak for themselves, but while we’re on the subject of quotes, David Phipps, our European Editor, had this to say about the 911’s handling: “Both directional stability and cornering are far better than they have any right to be in a car which has the engine in the extreme rear. In corners, you can forget all the things you have been told about the sudden, vicious oversteer of rear-engine cars. The 911’s handling characteristics are basically neutral, progressing to slight understeer. It takes a ham-fisted clot to upset the back end in the dry, and even in the wet you will only get the tail out by using lots of revs in the lower gears.”

The 911 performs better than any previous street Porsche, including the two-liter Carrera. It’s kind of a pocket battleship: What it can’t out-accelerate it can out-handle, and what it can’t out-handle it can out-accelerate. There probably aren’t five comparable sports/touring cars in the whole spectrum that could lap a road course faster than the 911. And—back to the pocket battleship analogy—those that could probably would fall by the wayside long before the Porsche expired.

The best gas mileage we could record flat-out on the Autobahn was 24 mpg, but oil consumption was minimal. The oil change interval is up to 3000 miles, and the number of grease fittings has been reduced to zero. There are no other surprises in the 911 for any driver familiar with Porsches. The fan noise and growl of an air-cooled engine are typically Porsche. Getting in and out—despite the wider doors—still requires a supple spine, and so on.

What Porsche has wrought in the 911 is a worthy replacement for all the models that preceded it. Race breeding and engineering refinement ooze from the 911’s every pore. The whole package, especially the powertrain, is designed to be more reliable and less difficult to service, thus all the better suited to the factory’s concept of the Porsche as a sealed machine for ground transportation. Although the 911 costs a lot less than the Carrera—and a lot more than the current C and SC—it’s worth the price of all the old Porsches put together. Most importantly, the 911’s appeal should be considerably wider than the earlier models—which, in truth, you had to be something of a nut to own. Anybody who ever felt a flicker of desire for a Porsche before will be passionately stirred about the 911.

Specifications

Specifications

1965 Porsche 911

Vehicle Type: mid-engine, rear-wheel-drive, 2+2-passenger, coupe

PRICE

As Tested: $6490

ENGINE

SOHC inline-6, aluminum block

Displacement: 122 in3, 1991 cm3

Power: 148 hp @ 6100 rpm

Torque: 140 lb-ft @ 4200 rpm

TRANSMISSION

5-speed manual

CHASSIS

Suspension, F/R: struts/semi-trailing arms

Brakes, F/R: 10.8-in disc/11.3-in disc

Tires: Dunlop SP

DIMENSIONS

Wheelbase: 87.1 in

Length: 164.0 in

Width: 63.4 in

Height: 51.9 in

Curb Weight: 2376 lb

C/D TEST RESULTS

60 mph: 7.0 sec

1/4-Mile: 15.6 sec @ 90 mph

100 mph: 20.0 sec

Top speed: 130 mph

FUEL ECONOMY

EPA city/highway: 16/24 mpg

C/D TESTING EXPLAINED