From the November 1969 issue of Car and Driver.

For the record, the de Tomaso Mangusta is mortal. It is a car assembled from workaday nuts, bolts, and aluminum castings just like every other car. That is what it is for the record; for the driver, it is high adventure.

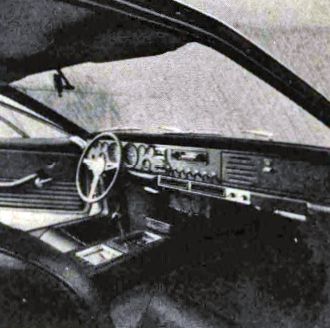

You sit low in the Mangusta, almost on the floor, in a bucket seat that allows no choices of posture. You stretch out for the tiny wood-and-leather steering wheel, while pale luminescent needles waver across seven black dials. The vast windshield sweeps back from the cowl to almost touch your forehead, and just behind your neck is a flat bulkhead, to block out the sound from the engine compartment but not rear vision. You are aware of heat, partly emotional and partly mechanical, and a murmur of the exhaust filters into the tightly sealed cockpit as the Mangusta skims nervously over the pavement. That is the visual and tactile Mangusta—but only a few can drive it, and only those few will ever know that the driver’s nerve endings do not contact absolute automotive perfection.

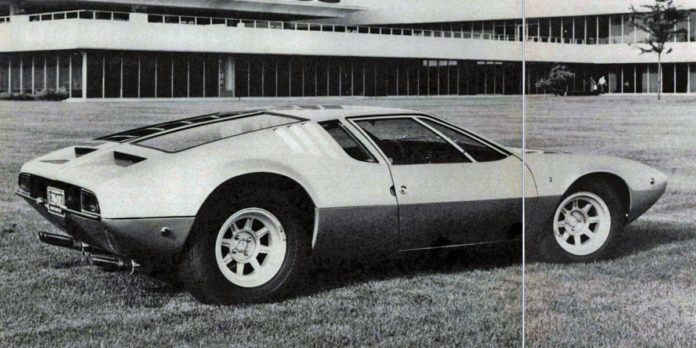

But anyone can watch—if only happy circumstance puts him in the right place at the right time—and to the beholder, the Mangusta’s mortal internals are of insignificant consequence. Rather than merely seeing a car go by, he is a witness to its passing, the Greek-like simplicity and beauty of its shape are stunning, and more often than not he is transfixed. It is only a car, to be sure, but its appearance is so powerful that it alters the life path of its driver and anyone else who falls within its magnetic field. Our experience within the first 24 hours couldn’t have been just coincidence. As we were parking, a young lady in a Pontiac suddenly realized she was terribly lost and wandered over for directions, consolation, and to show us she wore no ring on the third finger of her left hand. Only moments later a police car screeched to a halt and backed up beside the illegally parked Mangusta. And then something that never happens happened. The cops—caught up totally in their vision—forgot to write a ticket. Only a few short hours later we had an invitation home to dinner from a remote business acquaintance—and why not? Having the Mangusta parked in your driveway is the next best thing to the entire Presidential motorcade. To 12-year-old boys it looms as a promise of the future—a Tomorrowland bustling with sleek forged-alloy and stainless steel machines. To 12-year-olds the Mangusta is clearly irresistible. They will dream about it and in dreaming fasten upon it, and their legacy will be a layer of fingerprints that J. Edgar Hoover couldn’t unravel in a year.

Such is the power of the de Tomaso Mangusta, the power to make its driver an envied and emulated man wherever he goes. And, in a day of convenient mind expanders that can be either smoked or swallowed, the Mangusta acquires its stimulant-like qualities from a legitimate source—the drawing board of Giorgetto Giugiaro (C/D, February, 1969), an automotive stylist whose rejects would be instant hits in Detroit. As other cars exist because of certain specialities—the Ferraris because of their excellent mechanicals, Detroit cars in general because they offer more convenience-per-dollar than anything else in the world, and Volkswagens because somehow they seem like the most car for the minimum cash outlay—the de Tomaso Mangusta exists because it is the most beautiful car in the world. Moreover, it is close enough to being a real car that it must be judged on its automotive qualities as well as its looks.

You will remember that the Mangusta has a first name—de Tomaso. Alessandro de Tomaso is an Argentinian of just over 40 years, an automotive innovator who has proven to be his own worst distraction when it comes to honing his ideas down to the point where they are suitable for production. His 10 years as a car builder have been punctuated with racing formula cars, building show cars, and producing some few, like the Vallelunga. In retrospect, however, it can be said that de Tomaso has done little to aggravate the world’s traffic problem. Still, fortunes change, and de Tomaso’s outlook took a sharp upward turn in 1967. At that time, through some near Balkan financial manipulations, an American firm, Rowan Industries, Inc., bought the faltering Italian coachbuilder, Ghia, and de Tomaso was named president—a perhaps not-so-strange coincidence since Mrs. de Tomaso is closely related to several high officials at Rowan. It wasn’t long after this that the Mangusta, which first appeared at the Turin Show in 1966, began to show signs of becoming a production car, even though production didn’t start in earnest until the fall of 1968. Now bodies are built in Turin on chassis from de Tomaso’s Modena plant.

We have said that the Mangusta exists for the beauty of its shape, and yet the chassis is something of a masterpiece in its own right. Of course, it is a mid-engine layout. No car could have so little overhang and taper down to its ends like that and still have an engine of any size anywhere but in the middle. The frame is a backbone arrangement (which de Tomaso has pioneered) and is singularly responsible for making the Mangusta about as habitable as any 43-inch high automobile could ever be. All of the car’s structure through the passenger compartment is a rectangular section—about elbow high and 10 inches wide—which doubles as a console. This means that there are no broad structural sills to crawl over and the bottom of the door opening is almost at floor level—all very easy for going ashore or deplaning or disembarking. Just behind the backbone, the frame branches out into rectangular steel tubing members to surround the engine and provide attaching points for the rear suspension.

All of the suspension, but particularly the rear, is done up very much like a CanAm car. With the exception of the front lower arms all of the suspension members are fabricated of tubing with adjustable, weather-sealed spherical ball ends at the pivots. Sliding spline halfshafts are used at the rear. The Mangusta’s suspension offers a particular lesson to those who accuse Detroit of using too much rubber. The Mangusta has none, and traveling over tar strips and on certain road surfaces is enough to prompt unknowing passengers to inquire with some urgency as to the source of all that noise. Fortunately, the road noise is of such a frequency that it doesn’t seriously interfere with conversation or listening to the radio, but it can be very annoying if that sort of thing gets to you. Engine noise, always thought to be a problem in mid-engine cars, is no more apparent in the Mangusta than in a conventional front-engine sports car.

Just behind the passenger compartment is a dead-stock Ford 302-cubic-inch 4-bbl. V-8 rated at 230 horsepower, the same engine that was optional on Mustangs in 1968. In European Mangustas you can have an extensively modified 289, but the U.S. emission laws preclude that sort of frivolous consumption here. The only visible attempt to squeeze a bit more power out of the U.S. version is a set of streamlined, short-branch exhaust headers that feed through very short exhaust pipes to a pair of dual-outlet mufflers just behind the rear suspension. The radiator is mounted up front and the coolant pipes pass through the cockpit at the bottom of the backbone. At low speeds you can occasionally hear water gushing through the tubes, a bit of audio entertainment denied you in your everyday front-engine exotica. A manually-switched electric cooling fan is provided for traffic situations.

One of the more serious problems with mid-engine cars that use front-engine-car engines is the location of the normal engine-driven accessories like the alternator, air pump for exhaust emission control, and the air conditioning compressor. You can make the wheelbase long and leave the accessories on the front of the engine in the conventional fashion, or you can try to keep the wheelbase to a reasonable length and move the pumps and things somewhere else. De Tomaso has chosen the latter. The Mangusta’s wheelbase is 98.0 inches, the same as the Corvette. The only room left for the pumps and alternator is at the rear of the block where they are belt-driven from a jackshaft that runs back along the top of the intake manifold.

Engineering problems like this tend to amplify the difficulty of designing a successful mid-engine passenger car. No one disputes that a mid-engine location provides favorable weight distribution for a racing car but, at first, the location of the engine entirely within the wheelbase in a car that is supposed to carry passengers and luggage seems like an irresponsible luxury. But think about it for a while. Any front-engine sports car that even approaches 50/50 weight distribution has its motor entirely behind the front-wheel centerline. The problem, then, simply becomes one of which end of the engine do you want the driver to sit on. In either case, you can only push him so far forward or so far aft until he is up against the wheelhouses, and this actually favors the mid-engine car because he can angle his feet in slightly to miss the front wheel space.

The Mangusta makes an excellent case for the mid-engine concept. Admittedly, the engine accessibility is difficult, but there is as much usable room for the driver and passenger in every direction but up, and as much luggage space as there is in a Corvette, and the Corvette is a full 14 inches longer. Space has been allotted carefully in the Mangusta and it shows. The spare tire (same size as the fronts) is stowed over the transaxle in the rear, and the battery is mounted in the extreme right rear corner. Between the right rear wheel and the passenger seat, flanking the engine, is the gas tank and a like-size space on the driver’s side is open for cargo. The real trunk is up front, a highly irregular-shaped compartment since frame members intrude in various spots, but enough for a reasonable quantity of luggage nonetheless.

Of course, all the luggage space in the world isn’t much consolation if you can’t fit into the cockpit, and if you are much over six-feet tall it’s going to be a problem. Legroom is plenty good enough, even though you’re obliged to point your limbs in toward the center of the car, but it’s your head that will get you every time. The driver’s seat in the test car had been lowered for a bit more clearance, but on the passenger’s side, a 6-footer’s head would rub on the roof. Part of this clearance problem stems from the Mangusta’s erect driving position—a sharp contrast to other mid-engine cars like the Lotus Europa and the Ford GT Mk III. However, the Mangusta has a great advantage over the other two in ease of entry and exit, since a reclining seat requires that the steering wheel be brought so far toward the driver that it is difficult to slide out from under.

Once you are in you’re immediately confronted by a miniature wood-rim steering wheel that is leather covered in the two sections where you are expected to grab a hold. The instrument panel has a gauge for everything you can imagine, all round, white-on-black Veglias marked in English, but most of the smaller ones are obscured by the plump steering wheel rim. In the Italian exotica tradition, there is an endless row (seven, actually) of toggle switches to summon every genie in the house. None of them can do anything about the most serious navigational problem of all, however, rear visibility. The Mangusta turns out to be one of those cars in which you pick a lane and drive in it until you have some very strong reason to do otherwise. The rear quarters are completely blind (the test car had no outside mirrors) and the inside mirror sees very little more than the rib that runs down between the two rear windows. Those stiff of neck will find the inside mirror a challenge in itself, since it’s on about the same latitude as the end of your nose and you have to turn your head almost completely sideways to see it.

Visibility isn’t the only factor that takes the edge of pleasure off of driving the Mangusta. The hydraulically-operated clutch is very stiff, although the pedal travel is commendably short, and the accelerator operates a cable throttle linkage that feels as though it’s been lubricated with gravel. Since the five-speed ZF transaxle is clear at the rear of the car, the linkage is necessarily remote and loses most of its accuracy in the process. The lever moves through a chrome-plated maze in the console with the top four speeds in an H-pattern and first gear to the left rear, outside the H. Almost invariably the system hangs up between first and second, and it takes a hefty push against a strong spring to engage fourth or fifth. To give you an idea of the closeness of the transmission ratios, third and fifth in the ZF are almost exactly the same spread as third and fourth in the close-ratio Corvette box—so you can see that fourth in the Mangusta is really splitting hairs.

Performance of the Mangusta is modest for several reasons. Even though the car weighs only 2915 pounds the stock 302 Ford V-8 was never known for its muscles. Partly because of the air pump and partly because of what felt like fuel starvation, this particular Ford was all done before 5000 rpm, and the best times were obtained by shifting at 4700. With all of these handicaps, a lethargic engine and a difficult shifter, 15.0 seconds at 91 mph in the standing quarter was the best the Mangusta could do.

Braking didn’t set any records either. Four-wheel disc brakes are used with vacuum assist but pedal pressure is still high. With more than 62 percent of the total weight on the rear wheels, they were the last to lock up, but it still took 297 feet (0.72 g) to stop from 80 mph. Even though the stops were made in a very orderly, straight-line manner, fade was apparent and the brake pedal bottomed out on the third try. We aren’t sure why the Mangusta doesn’t stop quicker but it’s barely adequate as it is.

If the Mangusta is meant to do anything it is meant to handle well, and its capabilities are certainly well above anything that can be used in polite traffic. To help contend with the rearward weight bias, tire capacity is also biased toward the rear with 185 HR-15 Dunlop SPs on 7-inch wide wheels in front and 225 HR 15s on 8-inch wide wheels at the rear. Since this test, except for the acceleration and braking phases at Detroit Dragway, was conducted entirely on public roads, some restraint was necessary in evaluating the handling. Early impressions with the tires inflated equally all around are that the Mangusta corners with much higher rear slip angles, which is to say a larger drift angle, than is normally found in a car wearing radial-ply tires. Further evaluations produced distinct oversteering tendencies with power, and the 4.5 turns lock-to-lock steering ratio makes for tardiness in trying to stay ahead of the wide swinging tail. (Inflating the rear tires to a higher pressure than the fronts would be helpful in obtaining a better balance.) So stiff are the anti-sway bars, both front and rear, that no matter what gymnastics we put the Mangusta through we were never aware of any body roll angle whatsoever. Even though the car is fairly sensitive to driver technique, we were cornering very rapidly, and there is no doubt that the Mangusta is capable of very high lateral acceleration rates.

Mid-engine location and Group 7- style suspension notwithstanding, it is to the man who likes intricate hand-built cars that the Mangusta will have the greatest appeal. Workmanship varies from good to excellent. All of the sheet metal, including the aluminum trunk lid and engine covers, which fold up like butterfly wings, is perfectly formed, and the silver paint was of show-car quality. Inside, the leather upholstery is simply and smoothly done with the bonus of a delicious hide smell that no living cow even suspected it was capable of. Then there are the little touches that you have to look for, like the complicated spring-and-lever device to hold the door open at full swing which works smoothly if not very well. And behind the instrument panel, under the clutch and brake master cylinder, which are located inside the cockpit, are, get this, sponge-covered trays to catch any leaks before they drip on your trouser legs. De Tomaso scores high with an eye toward the inevitable.

Unfortunately, some of the more crucial devices aren’t quite so well worked out. In low-speed operation, particularly with the cooling fan and air conditioning on, the battery finds itself in a deficit spending situation which it will tolerate for only the shortest of terms. At one point during the test, we had to enlist the aid of two highly paid photographers to push the Mangusta over to the edge of a hill so we could coast down to get it started. The problem appears to be a slow pulley ratio for the alternator drive since the system doesn’t start to charge until about 1300 rpm.

The Mangusta’s air conditioning reminds us of a conversation with Peter Monteverdi when he was being criticized about the amount of space the air conditioner occupied in the console of his new four-seater 375L. “All of the other European manufacturers can keep their air conditioners pretty much out of sight, so why can’t you?” was the essence of our rude question. He nodded, smiled broadly and said through his interpreter, “It’s true that you can’t see the others, but you can’t feel them either.” That certainly describes the Mangusta. The vast, sloping windshield makes the cockpit very much like a radiant hot dog cooker and the occupants are the hot dogs. The air conditioner can barely keep up with the heat coming in through the glass, not to mention that generated by the engine and the general warmth of the day. All of this is little wonder when you see the .049 McCoy-size compressor hanging off the engine.

Just to see if these problems were chronic we called Kjell Qvale, an irascible West Coast car merchant who, behind the shingle of British Motor Car Distributors. Ltd., is the American importer of the Mangusta. He was quick to agree that the air conditioner was a joke but explained that there had recently been a change from a Tecumseh compressor (which was used in the test car) to a higher capacity York which made a significant improvement. He also allowed as how some reshuffling of the alternator drive pulleys had revitalized the electrical system. We hope he is right.

Those of you who think of the Mangusta as a rare commodity are in for a surprise. Qvale claims to have brought 130 cars into the U.S. since last fall, roughly half of the total production and expects to continue in at least this volume until the exemption from the federal safety standards expires in 1971. Right now the Mangusta doesn’t meet any of the standards and there is a plaque to that effect, signed by de Tomaso himself, in the trunk. In fact, the car doesn’t even have seat belts, which is inexcusable, no matter what exemptions are invoked.

As a car the Mangusta has character, but it is hardly what you would call gentle on either mind or body. It does, however, present an opportunity to pick up a brilliantly contemporary piece of automotive sculpture for only $11,500. There are other cars we would rather drive but none we would rather be seen in.

Specifications

Specifications

1969 De Tomaso Mangusta

Vehicle Type: mid-engine, rear-wheel-drive, 2-passenger, 2-door coupe

PRICE

Base/As Tested: $11,500/$11,685

Options: AM/FM radio, $185.

ENGINE

pushrod V-8, iron block and heads

Displacement: 302 in3, 4950 cm3

Power: 230 hp @ 4800 rpm

Torque: 310 lb-ft @ 2800 rpm

TRANSMISSION

5-speed manual

CHASSIS

Suspension, F/R: control arms/control arms

Brakes, F/R: 11.5-in solid disc/11.0-in solid disc

DIMENSIONS

Wheelbase: 98.4 in

Length: 168.3 in

Width: 72.0 in

Height: 43.3 in

Curb Weight: 2915 lb

C/D TEST RESULTS

60 mph: 6.3 sec

1/4-Mile: 15.0 sec @ 91 mph

100 mph: 18.7 sec

Braking, 80–0 mph: 297 ft

Roadholding: 0.72 g

C/D FUEL ECONOMY

Observed: 14–16 mpg

C/D TESTING EXPLAINED