From the June 1969 Issue of Car and Driver.

The test questions have all been asked and it’s time for the Ford Motor Company to hand in its paper. Passing or failing will be determined, as much as anything, by the way the Mustang Boss 302 maintains its dignity on Ford’s handling course, a serpentine stretch of asphalt in the middle of what could pass for one of Dearborn’s golf courses. And right there it is, parked, or rather poised, at the entrance to the track—Ford’s answer to the Z/28. The mood is tense. Matt Donner, principal engineer in charge of Mustang/Cougar ride and handling, waits, anxious to have the Cobra Jet Mach 1 blot removed from the record or at least superseded by something a bit more meritorious.

Two slightly worn crash helmets are produced from the back seat, one for Donner and one for our technical editor, doing nothing, to dilute the battle-to-the-death atmosphere that strengthens as the moment for the shoot-out approaches. The Mustang doesn’t help much either, sitting there like a cocked .357 Magnum ready to do its specialty with no more than a nudge. Donner assumes his battle station behind the wheel. We will judge the first round from the passenger side. Seat belts; click. Shoulder belts; click. Key in the slot, turn . . . and the Boss 302 awakes with undisguised belligerence. Nose out on the track, first gear, second, third and a low anguished moan from the fat Goodyears as the Mustang threads into the first turn. Two necks strain to keep their heavy, helmeted heads balanced on their respective shoulders. Into the next turn, a tight 200-foot radius left hander, tail hung out and the inside front wheels clipping the grass at the apex. Left turn, right turn, lap after lap at exhilarating speeds—Donner is submitting his homework in a most convincing fashion.

Our turn. Easy at first, remembering the beak-heavy Mach 1 that plowed straight on with its front tires smoking if you tried to hurry. But the Boss 302 is another kind of Mustang. It simply drives around the turns with a kind of detachment never before experienced in a street car wearing Ford emblems. Faster and faster, but its composure never slips. Adjust the line with the steering wheel or with the throttle or both. Hang the tail way out with a quick flick of the wheel and a legful of gas. Do whatever you like and the car complies with the accuracy of your shadow. Very simply, the Boss 302 is unshakable. Maneuvers that had been highly unsettling in previous Mustangs have a recreational air about them in the Boss 302. The car understeers, but not much—it has just exactly the right balance to allow you to drive instead of plow through a turn. The steering responds to corrections right up until you chicken out, and the car’s attitude in a turn is extraordinarily sensitive to power. This is not to say that you spin out if you dip too deeply into the gas, but rather that you can order up and sustain any drift angle you like. Even better, the handling characteristics remain the same whether you’re cornering at six- or nine-tenths of the car’s ability. Without a doubt the Boss 302 is the best handling Ford ever to come out of Dearborn and may just be the new standard by which everything from Detroit must be judged.

While we’re all reeling from this unexpected development perhaps we should retrace our steps back to the beginning and examine Ford’s motives for such an advancement. You see, there is this thing called the youth market which appears to have an insatiable appetite for wildly trimmed performance cars and can summon up the cash, or at least the monthly payments, to indulge itself. Chevrolet has always been particularly sensitive to these youthful demands.

When Ford discovered that Chevy sold 7,000 Z/28 Camaros in 1968, and the marketing demographers predicted that up to 20,000 might be sold in 1969, there was no choice but hoist the bugle and blow the charge. Not only was Chevrolet selling cars to customers who might have bought an equivalent Mustang if it was available, but Chevy was also achieving a fantastic reputation every time the David-like Z/28 dusted off somebody’s, and maybe one of Ford’s, Goliaths. It’s not that Chevrolet had created a particularly conspicuous automobile, but the Z/28’s combination of endearing mechanical presence and sparkling performance had made it the car for those in the know.

Ford needed the Boss 302 for one other reason. The SCCA says that for any trick part to be legal in the Trans-Am it has to appear on at least 1000 street cars. That means that spoilers or aerodynamic improvements of any sort, and high performance engine parts like blocks and cylinder heads, will have to be at least limited production items. Building just a handful of parts like last year’s 302 tunnel-ports is definitely verboten. So, since Ford has to build at least 1000 of these pseudo-racers if it wants to play in the Trans-Am, it might just as well make them visible and attempt to chock the wheels of the fast selling Z/28.

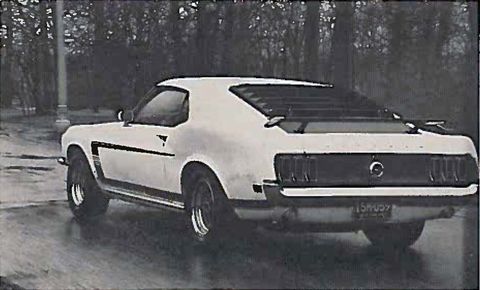

Those are the reasons, but in Detroit’s war of model proliferation to compete with, and get ahead of, everybody else’s model proliferation, Ford has treated itself to a healthy escalation. The Boss 302 is a bell of an enthusiast’s car. It’s what the Shelby GT 350s and 500s should have been but weren’t. Ford stylists have done an admirable job in creating a visual performance image for the Mustang variants this year and the Boss 302 is no exception. It’s clearly a Mustang but distinctly unique at the same time.

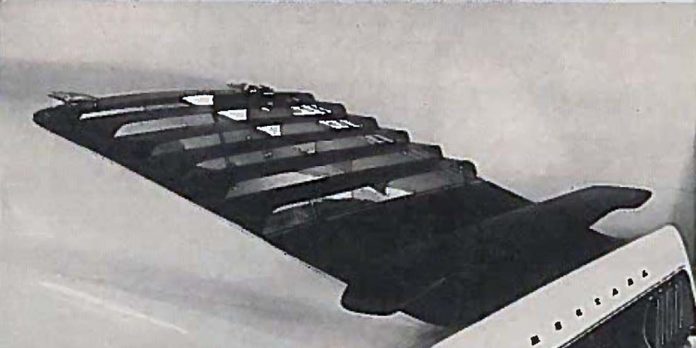

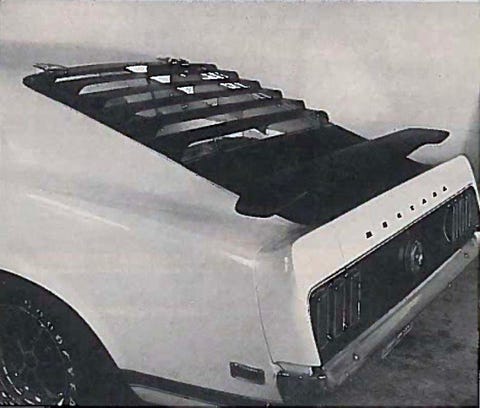

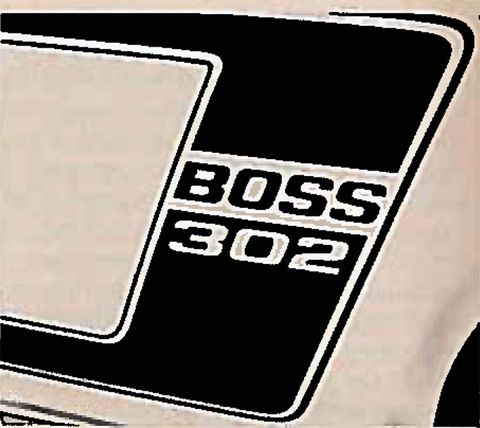

Matte black paint applied to the hood, rear deck and around the headlights is a standard part of the package, as is the tape “C” stripe with the Boss 302 insert on the side of the body. Since the shovel-shaped spoiler under the front bumper works, at least on the race track, it is standard equipment, too, because Ford wants to make sure 1000 of them are sold before the first race. Something the less astute might not notice is that the scoop just below the rear quarter window has been filled in. As Jacque Passino said, “The purist car people expect scoops to scoop something, and since that one didn’t it had to go.” The real visual sauce—the venetian blind “sport slats” on the back window and the adjustable wing on the rear deck-is optional. The slats are actually a one-piece arrangement, hinged at the top and latched at the bottom, so it can be tilted up before washing the rear window.

Styling is only a fraction of the Boss 302’s story. The engine, since it is the basis for the Trans-Am racer, has not been neglected. Every spring it’s time for the annual changing of the cylinder heads in Ford’s performance department. Last year’s tunnel-port racing setup is being replaced by a brand new design which has canted valves much like Ford’s street 429 and Chevrolet’s 396-427. Tunnel-ports are out but big valves are in. The intake valves, with a diameter of 2.23 inches, are only 0.02 smaller than those in a Chrysler 426 Hemi. Ports, too, are generous in size. The new heads are intended for racing as well as street use and will fit the 302 and 351 V-8s as well as all the 289s currently running around on the street. Other 1969 features include new pistons to conform to the new combustion chamber shape and 4-bolt main bearing caps for bottom end strength. An aluminum high rise intake manifold with a 780 cubic-feet-per-minute Holley 4-bbl. tops off the package. Ford rates the output at 290 hp (same as the Z/28) @ 5800 rpm, and no one will dispute that it makes at least that much. Standard with the engine is a wide ratio (2.78 first gear) transmission and a 3.50 axle, which strikes us as an ideal compromise for both low speed acceleration and comfortable expressway cruising.

New engine notwithstanding, it’s the Boss 302’s handling that makes the car outstanding and it was accomplished with relatively few changes. Most visible is the tires—Goodyear F60-15 polyglas balloons that put more than eight inches of rubber on the road-mounted on 7-inch wide wheels. The tires are so wide that special front and rear fenders, with revised wheel openings and reshaped rear wheel houses, had to be designed for the Boss 302. To clear the front suspension also required that the wheels be offset farther toward the outside of the car which, in turn, required new front spindles with larger wheel bearings. Fat tires have to really grip the pavement to be worth that much trouble—these do.

The Mustang’s new-found handling ability demanded a greater revision of the engineering department’s philosophy than it did of suspension parts. Kicking the understeering habit is no easier than giving up the weed or peyote nuts and Ford is to be commended on its rehabilitation. One thing was in its favor from the very start and that is weight distribution—55.7% on the Boss 302’s front wheels compared to 59.3% for the 428 Mach I. But there is more yet. Front springs and anti-sway bar are softer on the Boss while the rear leaf springs are stiffer—all of which tends to reduce understeer. Shock absorbers and the suspension geometry is carried over with no modifications.

Whether you order manual or power steering, the gear ratio is the same, at 16-to-one. The test car, with its manual steering, never could be accused of a Jack of road feel when we were flailing. Unfortunately, in this crowded world, you can’t flail much and still keep a good grip on your driver’s license, and power steering is far better suited to routine traffic situations. We’ve driven far worse manual steering cars but parking the Boss 302 is still equal to about six push-ups.

The Boss 302 we drove is an engineering prototype and the only one in existence at press time. In fact, it had been in Ford’s wind tunnel to check the effect of the rear spoiler just before our session at the test track. Normally we avoid doing a full road test on a prototype because it might not be typical of a production car, but in this case the weatherman didn’t even give us a chance. The rain started between the handling course and Detroit Dragway, where the acceleration and braking parts of the test were to be conducted, and didn’t stop for the rest of the day. For that reason the performance data on the specification page has been calculated from information supplied by Ford’s engineering department—definitely not our normal procedure but better than nothing. We do have some very distinct driving impressions other than those on the handling course however, which should be passed along. Ride quality is toward the stiff side, particularly in the rear which crashes with vengeance over big irregularities in the road. Still, considering the handling, it’s a good trade out.

When you speak of engines in this class of car the Z/28, with its nervous and jerky deportment and ultra-quick response in the 12-cylinder, dohc, Italian fashion, is the standard of comparison. The Boss 302 has a temperament completely unlike its competitor. It idles smoothly and quietly with almost no mechanical noise and has average response, neither quick nor slow. It could easily find a home in a Falcon and no one would be the wiser, at least until the Holley’s secondaries snapped open. Ford claims that its new little motor actually makes more power than the Z/28 but, subjectively, the car doesn’t feel quite as fast. Certainly it doesn’t have the slightly tamed racing car personality which has won the Z/28 throngs of friends. Ford engineers even volunteered that the Boss can be readily launched in second gear and they’re right—for whatever that’s worth in your racer replica.

Roaring around Ford’s test track and splashing through Detroit from suburb to suburb has made believers out of us. If the production cars are anywhere near as good as the prototype, the Boss 302 is easily the best Mustang yet, and that includes all of the Shelbys and Mach ls. After receiving no recognition other than gold stars for attendance in our road tests for the last several years Ford has learned its lessons well. The Boss 302 Mustang earned itself an A for this semester.

Specifications

This content is imported from OpenWeb. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.