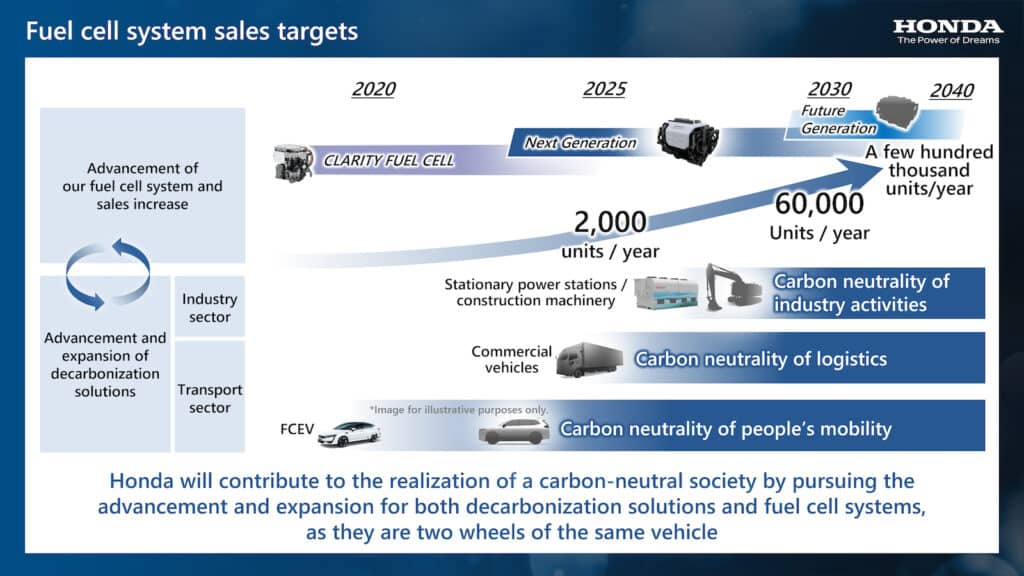

Honda is betting billions it can make fuel-cell technology a major alternative to batteries. It recently announced plans to introduce a hydrogen-powered version of its popular CR-V crossover next year. But in a media background briefing this week, a senior Honda official revealed a much broader target for the technology.

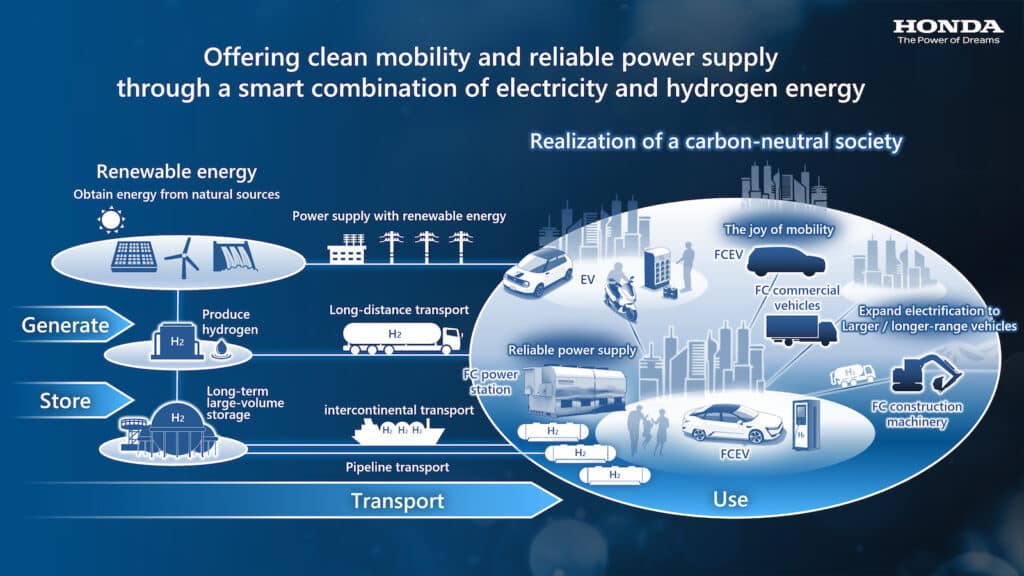

Over the coming decade, the automaker envisions a growing opportunity to use hydrogen as a fuel for everything from commercial trucks to aircraft. And it sees widespread opportunities to use fuel-cell for both stationary and portable generators and energy back-up devices. That could include large-scale systems able to help stabilize the flow of power from commercial-sized renewable systems such as wind and solar farms.

Honda is “thoroughly committed” to hydrogen technology, and believes it is becoming increasingly competitive as costs comes down and the practicality and reliability of the technology rapidly improves, said Ryan Harty, the senior manager of Honda’s Energy Solutions Business Division.

A long history

The fuel-cell was invented way back in the 1850s. At its most basic, the technology combines hydrogen and oxygen in a device called a stack. In the presence of a catalyst, such as platinum, they combine to form water vapor. In the process, electrons are stripped away and can be used to power the same electric motors found in an EV — or to power a home, office or worksite.

The technology only saw its first commercial application develop as part of the Apollo lunar program where fuel-cells provided power for manned capsules headed towards the moon.

Honda began working on the technology in the 1980s but only brought it to market in the form of the original FCX fuel-cell vehicle. It followed with the 2008 FCX Clarity and a more efficient version released in 2016.

Next-generation technology

Clarity ended its production run during the 2021 model year. But Honda officials in Japan last week announced an even more advanced system will go into production in 2024 powering a version of the carmaker’s popular CR-V crossover.

The new fuel-cell “stack” will come in at barely a third of the cost of the prior-generation technology, and is expected to be more efficient, more reliable, and able to operate at substantially lower temperatures.

Plenty of opportunities

But during this week’s media briefing, Harty revealed that passenger cars are just one of four key areas where Honda believes hydrogen technology can play a major role. The other areas include:

- Commercial vehicles where fuel-cell technology could match or exceed the capabilities of today’s diesel engines “in terms of ease of use and total cost of ownership,” said Harty;

- Construction equipment, such as bulldozers and other heavy lifters. There are already limited applications in use, including forklifts;

- Power management systems as small as home generators and as large as power backup systems that could help store energy for renewable systems like wind or solar farms.

Honda already has a substantial grip on the lower end of the power management business as one of the world’s largest producers of portable and stationary generators.

Growing competition

The automaker is by no means the only company looking at applications for fuel-cell technology. BMW is beginning a pilot program using the lightweight gas to power its X5 sport-utility vehicle and could expand that into a larger retail program.

Both Hyundai and Toyota sell their own fuel-cell passenger vehicles. And they’ve both launched pilot fleets of hydrogen-powered trucks aimed at reducing emissions at the smoggy Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Meanwhile, startup Nikola plans to start delivering fuel-cell trucks to commercial customers later this year.

Hyundai also is looking at a variety of other mobile and stationary applications. So is General Motors which last year launched a line-up of hydrogen-powered generators. It’s entered in a joint venture to prototype fuel-cell-powered locomotives, as well.

Honda teams up with GM

Honda and GM developed their newest fuel-cell systems as part of a joint venture pooling their individual research and development efforts.

Harty would not say whether the two manufacturers will, going forward, work together to commercialize the technology. Nor would he reveal whether that joint venture will now continue as Honda sets out to develop even more advanced and lower-cost hydrogen technology.

Even as the cost comes down, and efficiency rises for the latest fuel-cell systems, Harty acknowledged there are some key obstacles to widespread adoption of the technology. For one thing, there’s the cost of the gas — typically about twice as much as gasoline on a per-mile basis. And that’s where hydrogen is available. There are barely more than 100 locations in the U.S. today where motorists driving the Honda Clarity or Toyota Mirai can tank up. And there aren’t many more places where commercial fleets can find the fuel, either.

The chicken and the egg

How to address this chicken-and-egg problem is a matter of debate. But, from Honda’s point of view, “We see (commercial trucking) as a key driver to expanding fuel cell (availability),” said Harty.

That’s because many of the fleet operators that could switch to hydrogen power run regular routes where it would be relatively easy to set up refueling stations. As their numbers expand, it would make it easier to service passenger car owners, as well as those who would use the gas for generators and other applications.

In the long run, Harty said there could be even more applications for hydrogen beyond using it in fuel cells. One approach would combine the gas with carbon dioxide recaptured from the atmosphere to create synthetic fuels for aircraft. That approach would mean no additional carbon dioxide emissions.

“Fool cells”

Not everyone is as gung-ho on hydrogen as Honda, however. Tesla CEO Elon Musk has dubbed the technology “fool cells,” though that might be no surprise considering his focus on battery power.

But even proponents acknowledge that while hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, it isn’t readily available here on Earth. It must be generated by either cracking fossil fuels, such as coal, petroleum or natural gas — a no-no for environmentalists — or produced by electrolyzing water. That means splitting the liquid into two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen.

That’s an easy process, but an energy intensive one. And, Harty acknowledged, the only way to use electrolysis in an environmentally friendly way will require the use of renewable energy in the first place.