From the November 1995 issue of Car and Driver.

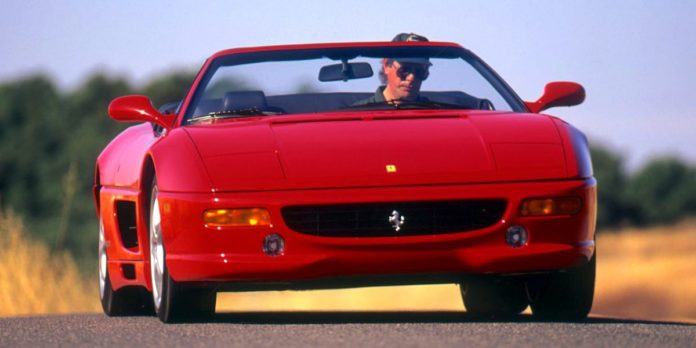

The Angeles Crest Highway is a favorite haunt of L.A.’s crazed sport motorcyclists, and as I wound the Ferrari F355 Spider through one looping uphill right-hander, a Honda CBR600 F3 whizzed by the other way, cranked over so far that there was just about an inch of clearance between its footpeg and the asphalt.

I was not trying that hard. At $139,091, the Ferrari is almost worth more than my house, and there was no protective metal over my head in the event of a tumble off one of the many reducing-radius bends bounded by little more than thin air. But I was running some of the sweeping curves at 90 or more, reveling in the accuracy and eloquence of the steering and the tenacity of the Pirelli P-Zeros. Best of all, though, was the serenade of engine noises issuing from just behind my head.

These melodies vary from a deep, resonant rumble at idle, to a flutelike tone in midrange, on to a healthy brasswind bellow at full bore. There’s an unusual harmonic at small-throttle openings—particularly noticeable in slow traffic—where the engine note drops momentarily into a deep grumbling overrun resembling the tones produced by the bass pedals of a Hammond organ.

The engine’s acoustic repertoire is so heroic that Ferrari does not even fit a radio to the F355 Spider as standard equipment. The boisterous sound effects, which are largely undiluted by the minimally insulated fabric top, produce sound-level readings at full throttle of 89 dBA, compared with 84 for the coupe.

Of course, it isn’t just for the engine note that one buys a convertible. it’s for the wind-in-the-hair experience, or perhaps to be seen in. Either way, the Ferrari does the job well.

The top mechanism is compact and simple. To doff the top, you simply unlatch the two attachment claws from the windshield header with a single handle, raise the front of the top until the car beeps at you, then nick a switch. That triggers a sequence that first pushes the seats forward six inches to provide clearance—disconcerting for those of us more than six feet tall—then powers the top down into a furled bundle behind the cabin, then returns the seats to their original positions. You have to get out to fit a fabric boot that snaps over the accordioned top to tidy the effect. Then away you go.

The car works well as a convertible. Additional structural bracing (it accounts for most of the 110-pound weight gain) has made the body shell commendably stiff, so there’s negligible shivering or jiggling to be found in the steering column, cowl, or windshield frame. And the aerodynamics are surprisingly good. Perhaps because of the windshield’s extreme rake, there’s hardly any wind buffeting. Nor is there much of that reverse draft you normally experience in choptop coupes. It’s so good that I could wear a baseball cap at speeds up to 100 mph without losing it to the slipstream. With the side glass down, the passing air produces an appreciable gush of sound, but it’s free of annoying fluctuations, and turbulence inside is so low that you can keep a map in your lap.

The Spider’s dynamic capabilities nearly equal those of the coupe that has earned accolades in two previous C/D tests. The 375-hp 40-valve V-8 hurls the Spider to 60 mph in 4.8 seconds and through the quarter-mile in 13.4 seconds at 106 mph. That’s a couple of tenths down on the coupe, probably due more to a relatively green engine than to the small weight increase.

In any case, the numbers don’t describe the sensation you get as the engine shrieks to 8500 rpm in every gear, or the rising urgency of the acceleration as the tach needle swings around to where the serious power lives. Nor does lateral acceleration of 0.96 g explain the communicative nature of the steering and the chassis. The Spider goes from neutral handling (with a remarkably supple ride) at cruising speeds to a lively tendency toward rotation near the limits of adhesion.

When the pace picks up, the front end begins to wiggle under hard braking and to produce quick lateral twitches in hard corners as the tires traverse surface irregularities. The back end begins to move around in hard corners too, eventually running wide at the limit. All of this is relayed to the driver in clear fashion, and the car is very responsive to changes in throttle position and weight transfer.

It’s this animated dialogue between driver and car that makes the Spider such an entertaining partner in the mountains, where the driver’s confidence is enhanced by a progressive and readable dynamic shift as the car approaches its limits. Loads of grip and bags of brakes don’t hurt either. And now that Ferraris have air conditioning that can be counted on and build quality that seems to improve with every new iteration, the appeal of the prancing horse is stronger than ever.

Only two small glitches: a blown cigarette-lighter fuse—no big deal—and a windshield-washer mechanism that dumped fluid into the ventilation system, producing clouds of alcohol vapor in the cabin but nothing on the windshield. A quick visit to the dealer would put that right, but it reminds us that handbuilt exotics will always have quirks.

It was unthinkable just a few years ago that Ferraris could ever become daily commuters, but this generation of F355s comes close. So long as you take care to avoid bottoming the low-slung, long-overhang nose on driveways and gutters, the F355 is tame enough to run to the office every day. Assisted steering makes the car much easier to drive at low speed, and the throttle stiction we grumbled about on earlier F355s is reduced in the Spider, allowing us to drive smoothly with minimal concentration.

The traditional gated six-speed shifter remains fairly notchy and mechanical, but you can drive almost seamlessly if you pay attention. And although you wouldn’t expect it from a car with an 8500-rpm redline, the F355 has more low-end grunt than a Porsche 911, giving it good around-town flexibility.

Most amazing of all was that the luggage compartment in the Spider’s nose swallowed my square Samsonite as if tailor-made for it. Okay, people don’t buy Ferraris for their practicality, but as long as a bit of creature comfort doesn’t hurt the visual appeal or the mechanical aesthetics or the knock-’em-dead status value of the marque, it’s fine with us. Now, if they could just do something about the price. . . .

Specifications

Specifications

1996 Ferrari F355 Spider

Vehicle Type: mid-engine, rear-wheel-drive, 2-passenger, 2-door convertible

PRICE

Base/As Tested: $139,091/$139,091

ENGINE

DOHC 40-valve V-8, aluminum block and heads, port fuel injection

Displacement: 213 in3, 3496 cm3

Power: 375 hp @ 8250 rpm

Torque: 268 lb-ft @ 6000 rpm

TRANSMISSION

6-speed manual

CHASSIS

Suspension, F/R: control arms/control arms

Brakes, F/R: 11.8-in vented disc/12.2-in vented disc

Tires: Pirelli P-Zero

F: 225/40ZR-18

R: 265/40ZR-18

DIMENSIONS

Wheelbase: 96.5 in

Length: 167.3 in

Width: 74.8 in

Height: 46.1 in

Passenger Volume: 47 ft3

Trunk Volume: 8 ft3

Curb Weight: 3380 lb

C/D TEST RESULTS

60 mph: 4.8 sec

100 mph: 12.0 sec

1/4-Mile: 13.4 sec @ 106 mph

130 mph: 21.5 sec

150 mph: 35.7 sec

Rolling Start, 5–60 mph: 6.1 sec

Top Gear, 30–50 mph: 8.5 sec

Top Gear, 50–70 mph: 9.0 sec

Top Speed (redline ltd): 179 mph

Braking, 70–0 mph: 166 ft

Roadholding, 300-ft Skidpad: 0.96 g

C/D FUEL ECONOMY

Observed: 15 mpg

EPA FUEL ECONOMY

City/Highway: 10/15 mpg

C/D TESTING EXPLAINED