Despite a parade of electric vehicles that can travel more than 300 miles on a charge, range anxiety remains a major hurdle to widespread adoption particularly in the US.

There is, however, a “no-duh” antidote to allay fears of being stranded mid-trip: put a charger on the car. While traditional hybrid vehicles use gas to turn the wheels, a new crop of cars are burning it exclusively to charge a large onboard battery. It’s a strategy one might expect from an 8-year-old’s brainstorm, and it’s not a particularly efficient solution or a cheap one. But in an age of janky charging infrastructure and fraught, polarizing politics, electric motors juiced by an onboard, gas-sipping generator could be a killer EV app.

“It’s giving the customer the functionality they want but still using electricity for most of your daily driving,” said John Krzeminski, an engineer whose Detroit-based Strange Development builds and tests powertrains for major car companies. Krzeminski expects a rash of range-extending hybrids to hit the road in the next few years, as auto executives try to engineer a solution for drivers who are both EV aspirational and skeptical.

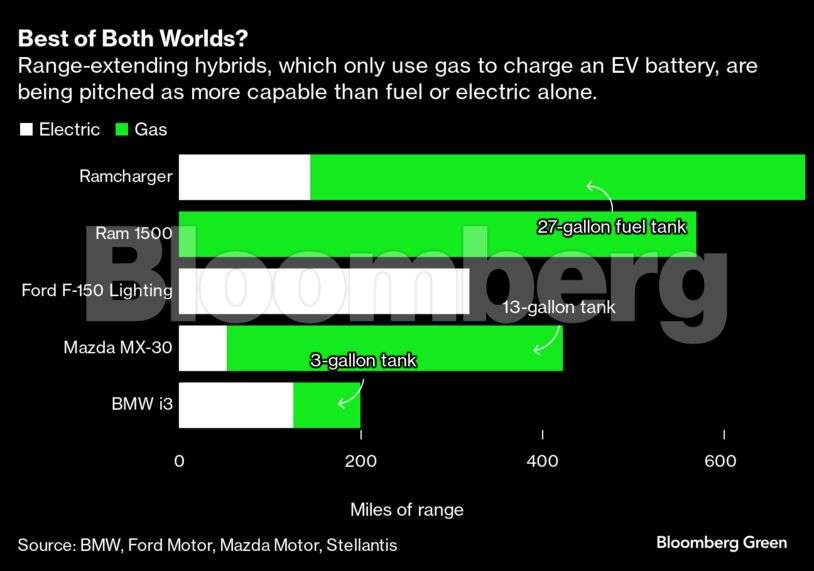

Consider the 2025 Ramcharger pickup that Stellantis NV is preparing to launch next year. The large-format truck will travel 145 miles on a 92 kWh battery, enough to cover most daily commutes and then some. It will, however, also have a 6-cylinder engine aboard to juice the battery while driving, acting as a charging station that works at 75 mph.

“Other people are looking at putting bigger and bigger and bigger batteries in,” explained Joe Tolkacz, a Stellantis chief engineer. “We looked at it and said, ‘OK, that works for some segment,’ but there’s another segment out there that says, ‘Hey, I’m not ready for a full electric truck yet. I’m used to driving a diesel where I can drive 600, 700 miles.’ And the Ramcharger provides that customer that capability.”

Range-extending hybrids aren’t a new idea. Bayerische Motoren Werke AG (BMW) brought the strategy mainstream in 2013 when it launched the i3, which offered a two-gallon, two-cylinder gas engine. BMW sold fewer than 50,000 of the machines — often at steep discounts — before scrapping the model in 2022.

However, the i3’s approach has aged well as charging infrastructure continues to be a huge roadblock to American EV adoption. The rig has garnered a cult following since it went out of production and resale values remain relatively high.

Make no mistake, a miniature, portable power plant is nowhere near as efficient as a utility version. An industrial power plant burns less than a tenth of a gallon of natural gas to generate a kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity. Once the battery goes dry on the nascent Ramcharger, the burly truck will slurp 27 gallons of gas to travel an additional 545 miles, which works out to a relatively anemic 20 miles of range per gallon of gas.

But while fossil fuels may be a curious catalyst for sparking EV sales, the strategy is arguably far greener than it looks. For one thing, Americans tend to vastly overestimate how much they drive while also vastly underestimating how many charging stations have come online in recent months. Once the gas engine kicks on, the new Ram trucks won’t be much more efficient than their internal combustion counterparts — in fact, they’ll be less efficient — but the trick is they won’t burn dead dinosaur juice very often.

“It’s fair to say consumers buy vehicles for their edge cases,” said Stefan Meisterfeld, vice president of strategic planning at Mazda Motor Corp., which is selling a range-extended version of its MX-30.

What’s more, making the massive battery — specifically, mining all the precious metals that go into it — remains the most carbon-intensive part of an EV. Battery-powered cars are still vastly cleaner than internal combustion machines, and they typically cross the break-even emissions threshold in less than two years. But a smaller battery significantly cuts the initial carbon footprint.

At 92 kWh, the Ram battery will be less than half the size of that of the GMC Hummer EV, the fully electric supertruck. (The Hummer EV also has the lowest green score on Bloomberg’s EV Ratings.) At a cost of roughly $139 per kWh, according to BloombergNEF estimates, Stellantis spends somewhere around $16,000 less on the Ram battery than General Motors does on its Hummer powerpack.

Krzeminski hopes that this will have broad appeal. “You’re getting electrification into more peoples’ hands at a much lower cost,” he said.

Mazda’s MX-30, meanwhile, comes with and without the range-extending engine. In Japan, more than two-thirds of buyers choose the version with the onboard generator; in Europe, it’s nearly half. The automaker is leaning in on hybrids, and Meisterfeld says the range-extending onboard generator is likely to show up in more Mazda models soon.

Those types of vehicles are “perfect solutions for people who are maybe 70% to 80% of the time perfectly fine with the electric range,” Meisterfeld said. “Ninety percent of the time or more, people probably won’t need more than 100 miles a day.”

Range-extending vehicles offer auto executives another unique value: help to navigate the culture wars. Battery-powered cars are a centerpiece of the Biden administration’s economic and climate policy. But there’s been backlash from former President Donald Trump, serving as fodder for his campaign rallies and recent speech at the RNC.

“I have no objection to the electric vehicle — the EV. I think it’s great,” Trump told Businessweek last month, shortly before listing several objections. “??The cars don’t go far enough. They’re very, very expensive. They’re also heavy.”

Some 77% of right-leaning voters said they were not interested in electric vehicles, up from 70% a year ago, according to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center earlier this year.

The Ramcharger and vehicles like it are basically designed to short-circuit EV biases while reaping many of the climate-saving benefits. Stellantis doesn’t have to change hearts and minds to sell its new Ram; climate deniers and Biden haters alike will enjoy the offset fuel costs even if they care little about melting ice caps and childhood asthma.

“It’s kind of like a Trojan horse,” Krzeminski said. “It’s almost kind of forcing people into a carbon reduction strategy just by meeting their needs for what the vehicle does.”

Ultimately, so-called range extenders will probably be a relatively brief and awkward pitstop — a vestigial limb not unlike ashtrays, CD players and carburetors. But for the moment, they stand to fill a fairly wide niche.

In nine years of driving his BMW i3, David Slutzky, has never gone far enough to trip on the gas range-extending engine. But it seems like a perfect solution for his wife, who is more inclined to road trip and more prone to range anxiety.

“She wants to have her cake and eat it too,” said Slutzky, the chief executive officer of Fermata Energy, a startup that builds vehicle-to-grid charging systems. He reckons there’s a significant crowd of like-minded drivers let down by fast-charging infrastructure, which is sparse, often broken and under-delivers on charging speeds.

“There are a lot of people who really want to go pure EV and can’t,” he explained. “Is (the range-extender) a stopgap? Yes, but to me it’s a stopgap that could be around for years.”