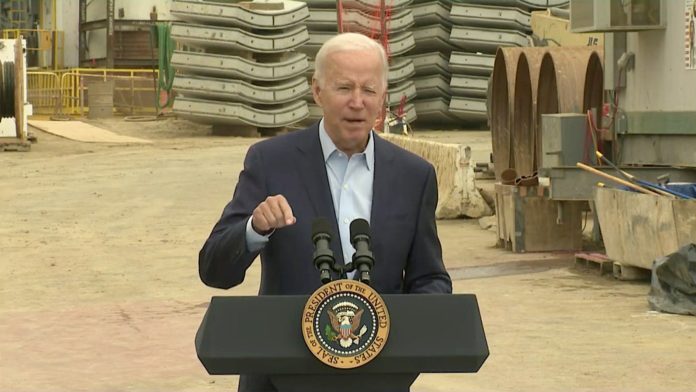

President Joe Biden is proposing to cut vehicle greenhouse gas emissions by 56% in 10 years, a move that would mandate that at least 60% of new passenger vehicles sold in the U.S. would be electric by 2030 and up to 67% by 2032.

This would require a huge increase in battery electric vehicle production. The plan calls for average yearly pollution reductions of 13% and a predicted fleet-wide average emissions reduction of 56% by 2026. Through 2032, the EPA is also recommending new — and more stringent — emissions requirements for medium- and heavy-duty trucks as well, with 46% of new medium duty trucks being EVs by 2032.

If finalized, the new requirement would dictate that two out of three vehicles sold by 2032 would be BEVs.

The government is working swiftly to finalize new regulations by the beginning of 2024, making it far more difficult for a future Congress or president to roll them back. The Biden administration undid President Donald Trump’s relaxation of strict pollution limitations that had been set through 2025 by his predecessor, President Barack Obama.

Is it enough?

As draconian as the new rules may sound, some are saying the proposal doesn’t go far enough. Dan Becker, director of the non-profit Safe Climate Transport Campaign criticized the move, saying that it falls short of the 75% pollution reduction needed by 2030.

“A stronger rule would save consumers more than a trillion dollars at the gas pump and cut our dependence on oil from problematic regimes,” Becker said.

What happens as a result

Nevertheless, the Biden administration’s 2027-2032 proposal would eliminate more than 9 billion tons of carbon dioxide emissions through 2055 — more than twice total U.S. carbon emissions in 2022.

The new regulation would cost $1,200 per car and manufacturer, but over an 8-year period, an owner would save more than $9,000 on gasoline, maintenance, and repair expense.

“A lot has to go right for this massive — and unprecedented — change in our automotive market and industrial base to succeed,” said John Bozzella, CEO of the Alliance for Automotive Innovation told Reuters.

And for the changeover to EVs to succeed, a lot of factors beyond automakers’ control have to change as well, and it starts with convincing consumers, many of whom remain skeptical.

Consumers remain unconvinced

A new poll by the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research and the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago shows that consumer acceptance is lagging, with 8% saying they or someone in their home owns or leases an EV, while 8% say their household has a plug-in hybrid vehicle. And that’s with a $7,500 tax credit towards the purchase of a new EV.

With that incentive going away this year for most EVs, the enticement to buy an EV is going away as well as they tend to be far more expensive to buy than conventional internal combustion engine cars. As of the beginning of the year, the average cost of an EV was $61,488, far more than the average price of $49,507 for all vehicles.

Perhaps that’s why a mere 19% of those polled say it’s “very” or “extremely” likely that they will buy an EV for their next vehicle, with 47% stating they’re unlikely to buy an EV for their next car.

Given that fewer than 6% of vehicles sold in 2022 were electric, reaching 67% within a decade seems to be a stretch.

Other factors

Consumer EV adoption and automakers’ ability to reach greater sales could be hampered by a lack of public and private EV charging facilities. For automakers, the ability to reach mandated sales means overcoming continued shortages of the raw materials like lithium and nickel required to create batteries.

Then there’s another shortage: places to recharge. A study by McKinsey & Co. reveals if half of all vehicles sold by 2030 are zero-emission vehicles, America will need 1.2 million public EV chargers and 28 million private EV chargers by then, or 20 times the number it has now. And charging at a public charger costs anywhere from five to 10 times more than doing so at home.

If 50% of new vehicle sales are EVs by 2030, McKinsey estimates that about 15 percent of all vehicles on the road in the United States will be BEVs, or about 48 million vehicles. That means the annual electricity demand to charge them would surge from 11 billion kilowatt-hours (kWh) now to 230 billion kWh in 2030, or 5% of total electric demand in the U.S. To meet that demand, 30 million chargers are needed at a cost of more than $35 billion.

And while the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law provides $7.5 billion to install 500,000 public chargers by 2030, according to McKinsey, that alone won’t go far enough to satisfy.

Though electric utilities say they can handle demand, recent events suggest otherwise. In September, California asked residents to not charge their cars during a block of time to avoid overloading the grid due to a heatwave, one that currently requires obtaining 30% of its power from other states. Californians were also asked to not run their air conditioners and several other items during that time.

And availability is a concern, as regulators are looking for electric companies to shut coal- and gas-fired plants, which will require new sources of power generation to replace them. That said, a KPMG study states that the U.S. currently has enough generating capability to charge 80 million EVs overnight.

But beyond power generation, there are added costs coming to transmit the power as it streps down from high-voltage lines to substations and neighborhoods.

Alleviating these other factors will play a key role in whether Biden’s proposal meets its deadline. The clock is ticking; there are 120 months.