The ability to produce lithium and other critical minerals necessary for mass production of EV batteries is an ongoing economic and energy security issue for the United States. That’s why recent legislation signed into lawstrongly favors domestic mining and production of battery minerals.

Right now, many of the minerals used to make EV batteries and rare earth magnets are mined in China. According to a 2021 report by Wards Auto, “China currently controls the processing of nearly 60% of the world’s lithium, 35% of nickel, 65% of cobalt and more than 85% of rare earth elements.”

Developing domestic mineral resources

Under the new U.S. laws, EVs must use batteries made in North America or certain partner nations, using minerals mined in North America or partner nations to qualify for tax credits. It’s a direct response intended to diminish Chinese control of critical resources.

The United States has substantial lithium deposits spread across the nation, and those remain substantially undeveloped. President Joe Biden has invoked the Defense Production Act to spur domestic mineral mining.

Through the mid-20th century, the United States produced most of the lithium in the world, but production declined when it became more affordable to buy lithium produced elsewhere. In recent decades, U.S. lithium mining has been taking place in desert areas of western states, where populations are sparse and most land is owned or controlled by the Federal government.

Currently the U.S. has only one fully operational lithium mine, located in Silver Peak, Nevada, which is responsible for less than 2% of annual global lithium production.

According to a 2022 paper issued by the U.S. Department of the Interior, “The clean energy transition will necessitate an overall 400-600 percent increase in global demand for key critical minerals like lithium, graphite, cobalt and nickel to meet our climate goals, and for some minerals the increase will be many times higher.”

Environmental and cultural challenges

However, the expansion of lithium mining is running into headwinds in the form of lawsuits by people who have deep cultural interests in those desert lands. Primarily, the resistance is coming from Native American tribes with historic ties to many locations where lithium may be mined.

According to a forthcoming paper in the Harvard Environmental Law Review, the issue runs deep with the potential for environmental damage to tribal lands. The paper is authored by Professor Lisa Benjamin, who teaches Environmental Law at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon.

“EVs have justice implications — both positive and negative,” Benjamin states. “The transition to EVs will have significant climate and environmental justice benefits for some communities, and negative impacts for others, including Native American tribes.”

Benjamin continues, “The vast majority of nickel, copper, and lithium are located within 35 miles of Indian reservations. Mineral mining has a number of environmental consequences. Lithium is located in salt beds, terrestrial brines, and clay. These geographic areas are often dry, but lithium mining relies heavily on water, and so can deplete scarce water resources which can threaten indigenous communities and ecosystems.

“Extraction techniques use acid and other chemicals to leach and separate out lithium, leaving mining waste which is often stored in tailing ponds. The process also leads to ground, water and air pollution from chemicals such as cadmium, arsenic, mercury and lead. Existing legislation does not provide sufficient protection from these negative impacts for surrounding communities, including tribes.”

A lawsuit over lithium

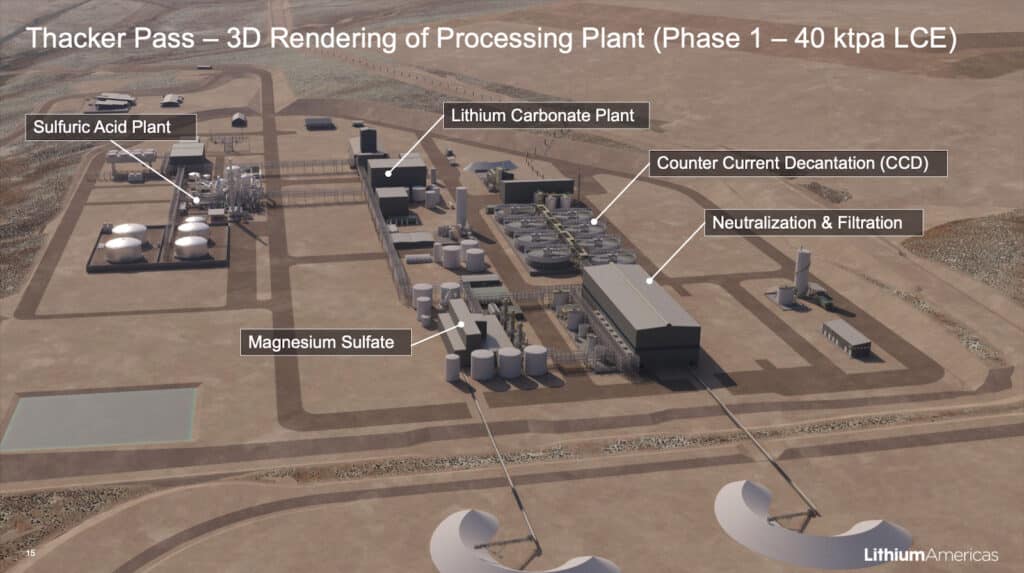

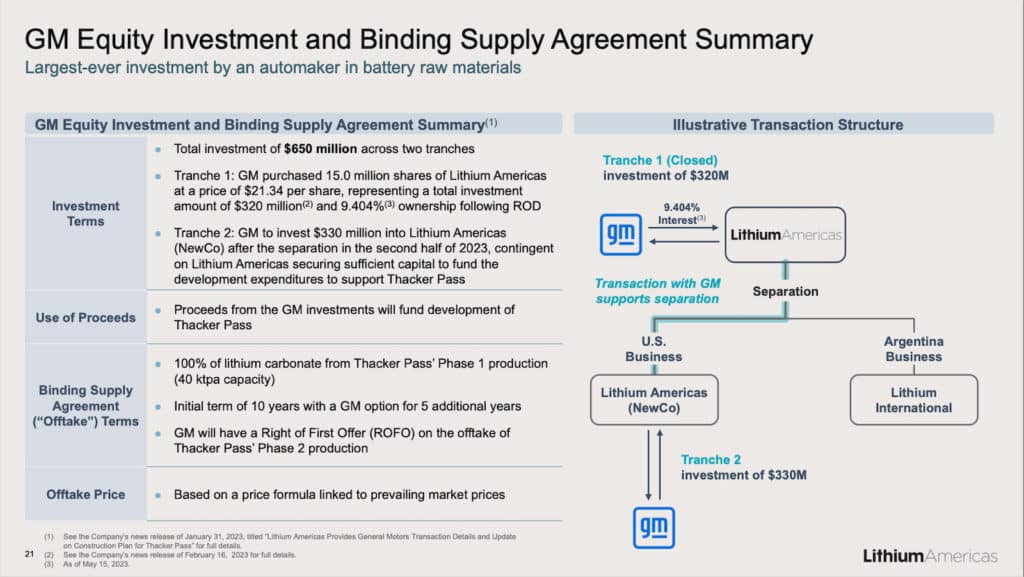

There is a pending lawsuit brought concerning lithium mining on Federal land near Thacker Pass, Nevada, known as Pee-hee-mm-huh to the nearby tribes. The mine is operated by Lithium Americas, with investment from General Motors. The location is the largest known source of lithium in the United States and the third largest in the world.

Under the agreement, GM has a $650 million equity investment in Lithium Americas, which represents the largest-ever investment by an automaker to produce battery raw materials. Lithium Americas estimates the lithium extracted and processed from the project can support production of up to 1 million EVs per year.

The suit against the mine was brought by Edward Bartel, a local cattle rancher, and joined by the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes, the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, as well as an NGO called the People of the Red Mountain.

Bartel and the other plaintiffs allege that the Environment Impact Statement filed by the Bureau of Land Management underestimated the groundwater pollution. The tribes further allege mining will take place too close to sacred sites, including burial grounds. The suit seeks to block Lithium America from opening a 1,000-acre mine plus another 1,000-acre facility to process hazardous materials including sulfuric acid.

The 1872 Mining Law

The lawsuit is bolstered by the “Rosemont Decision,” a 2021 ruling by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals that denied the government’s claim that the 1872 Mining Law conveys the same land use rights of a mine to use adjacent land to dispose of mining waste. The decision holds that the mining interests must prove that the adjacent lands also hold valuable minerals in order for those lands to be used for any mining purpose, including disposal.

According to an Associated Press report, “U.S. District Judge Miranda Du in Reno adopted the new standard in a ruling in February that found the U.S. Bureau of Land Management failed to comply with the law when it approved a Canadian company’s plan to open the Thacker Pass mine.”

“Despite that ruling — and over the objections of environmentalists and tribes who now are appealing to the 9th Circuit — Du allowed construction to begin at the mine while the agency provides additional proof the company has the mineral rights necessary to dump waste rock and tailings from the operation on adjacent federal land.”

The Thacker Pass litigation may have far-reaching effects on other mining operations. Currently, there are dozens of lawsuits pending across the nation seeking to stop mining operations. Interpreting an 1872 law to apply to 21st century mining with national security and civil rights implications will not be quick or easy.

For Professor Benjamin, justice is central to the controversy.

“While new regulations by the EPA, NHTSA and the BLM would be important components of a just EV transition, environmental and racial justice are complex regulatory problems, and these new rules may not do enough, on their own, to address all elements of environmental justice,” she said.

“While administrative law does pose constraints to justice-oriented agency action, these constraints are not insurmountable. Agencies have both regulatory and non-regulatory options available to them. They should exercise all of these options to ensure that the transition to EVs is a just and equitable one.”