Within barely eight years, as many as two out of three new vehicles purchased by Americans will be battery-electric models, at least if new emissions ruled unveiled by the Environmental Protection Agency this week withstand the inevitable legal challenges.

EV sales have grown rapidly in recent years, starting from a mere 1% in 2019 to 5.8% in 2022. And the numbers appear to be running north of 8%, according to preliminary sales data for this year, according to J.D. Power. With dozens of new all-electric models coming to market in 2023, and still more next year, experts forecast the growth rate is taking a hockey stick upturn and will likely hit 20% by mid-decade.

Yet, that number would have to grow fast, and while bringing yet more EVs to market will certainly help drive higher consumer acceptance, that’s far from the only obstacle ahead. Some are familiar: range anxiety, for one, as well as the substantial premium buyers currently pay for all-electric models.

Others involve addressing long-standing infrastructure problems: ensuring the grid can supports tens, even hundreds, of millions of EVs, both by providing the energy, as well as places to plug in. And the changeover also raises substantial geopolitical and national security issues.

Winning over consumers

Not long ago, about the only folks who seemed interested in EVs were environmentalists and those looking for the latest technologies. That’s begun to shift, a new Reuters/Ipsos poll finding 34% of American motorists “interested” in buying an EV. A separate Gallup poll released this week set the number at 43%.

The half-empty counterpoint is that 31% of those who responded to the Reuters/Ipsos answered with a firm “no, thanks.” And it was an even higher 41% using Gallup’s findings.

Optimists are quick to point out the number of those interested in buying an EV has grown by substantial multiples compared with the results of surveys taken just five years ago, and many experts believe the figure will continue to grow.

One reason is the “butts-in-seats” philosophy espoused by General Motors President Mark Reuss. He is convinced that when motorists actually get behind the wheel and experience the comfort and performance the newest EVs offer they will be won over. That’s backed up, to varying degrees, by both public and proprietary research.

More EVs, better EVs

One reason why is that today’s EVs offer more power, better range, quicker charging than their predecessors from even two years ago — as well as near-silent motoring.

Exotics like the Pininfarina Battista are turning out four-digit horsepower ratings and even the more mainstream Kia EV6 GT pushes out 576 hp. Where a decade ago early EVs like the Nissan Leaf struggled to top 100 miles per charge, Today’s baseline is 200, with more and more new models hitting the 300, even 400 benchmarks. The Ram 1500 Rev unveiled at last week’s New York International Auto Show will make 500 miles per charge with an optional 229 kWh battery pack, company officials boasted.

The Rev won’t reach showrooms until early 2025. By then, however, there will be nearly a dozen different all-electric pickup trucks on the market, including the currently available Ford F-150 Lightning, GMC Hummer EV and Rivian R1T.

And that addresses another obstacle. Early EVs were small, slow and, in many cases, weird looking. They didn’t come close to addressing the broad range of product segments American motorists shop for. That’s changing rapidly, with more vehicles in more current niches, as well as a few new ones.

Driving down costs

A funny thing happened on the way to showroom last year. Well, maybe not so funny. After falling for more than a decade, battery prices jumped substantially, to an average of $153 a kilowatt-hour. That adds up when most current EVs use packs rated at anywhere from 60 to 120 kWh or more. Why? Hang tight. But what matter most immediately is that all-electric vehicle prices increased even faster than for conventional models. They currently stand at $61,488 for the EV compared to $48,681 for a comparable gas-powered vehicle.

The numbers are a bit misleading, as electrics tend to target more premium market segments and usually come standard with more equipment. On the flip side, they generally have lower operating costs — including routine service, maintenance and energy — and many still qualify for up to $7,500 in federal incentives.

There’s a general consensus that last year’s surge in battery costs will level off and, at least by 2024, should start tumbling again. GM, for one, has publicly set a goal of driving the numbers down to $100 per kWh or less. And the Boston Consulting Group has forecast the late-decade numbers should be in the $70 range, especially if next-generation solid-state batteries work on the road as well as in the lab. For a typical midsize SUV, that would yield $5,000 or more in factory savings. And there is a broad consensus in the industry that EVs, by 2028, or soon afterwards, will actually be the cheaper choice.

National security

Back to that earlier question: why have battery costs skyrocketed? Because the key ingredients — lithium, manganese, nickel and cobalt — are traded as commodities. And, with such massive orders, prices have skyrocketed. Before the surge began in early 2021, lithium routinely came in at around $50,000 a ton. It peaked at just over $600,000 last November. It’s all but crashed since then but still commands $202,000, according to TradingEconomics.com’s tracking data. Similar stories can be told about those other fundamental elements.

The challenge is finding a ready supply of those materials. Make that a ready supply from friendly sources. And here’s where EV mandates become a political football. Opponents, including some key Republican officials, are quick to point out that China is a key source of many of these materials — starting with the vast majority of refined lithium. With relations between the U.S. and the Asian giant continuing to sour, there’s a concern that a switch to EVs could leave the country even more dependent than ever.

What often gets ignored is the fact that the U.S. is highly dependent upon unreliable allies for much of its petroleum needs, as recent spikes at the gas pump have demonstrated. The energy shocks of the 1970s should not be forgotten. Nor the fact that China provides plenty of critical materials for gas-powered vehicles, like the platinum needed for catalytic convertors.

Here’s where the IRA comes in again

The Inflation Reduction Act aims to address this — and not just by tossing money at the problem. Revised consumer EV incentives require that not only must qualified vehicles be assembled in North America, but their battery packs, as well. New rules set by the U.S. Treasury Department also require those raw materials come from the U.S., Canada, Mexico or a select group of other preferred trade partners.

“So far, 17 new EV battery facilities have been announced, aided by the latest round of Federal incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act,” Bank of America Securities Research Analyst Andrew Obin wrote in a Feb. 22 report to clients. Several others have since been announced, with all the plants now scheduled for just the U.S. and Canada to have capacity to energize anywhere from 10 million to 13 million EVs.

Spending is equally aggressive on the hunt for raw materials. GM alone announced a $650 billion investment in Lithium Americas in January, and another $50 million investment this week in EnergyX.

Will the industry be able to source enough of these minerals — and soon enough? That remains to be seen, and there are plenty of roadblocks here, as well. Ironically, some of the very same environmental groups demanding higher EV mandates are already trying to block some of the mining programs meant to supply raw materials for batteries.

Charger anxiety

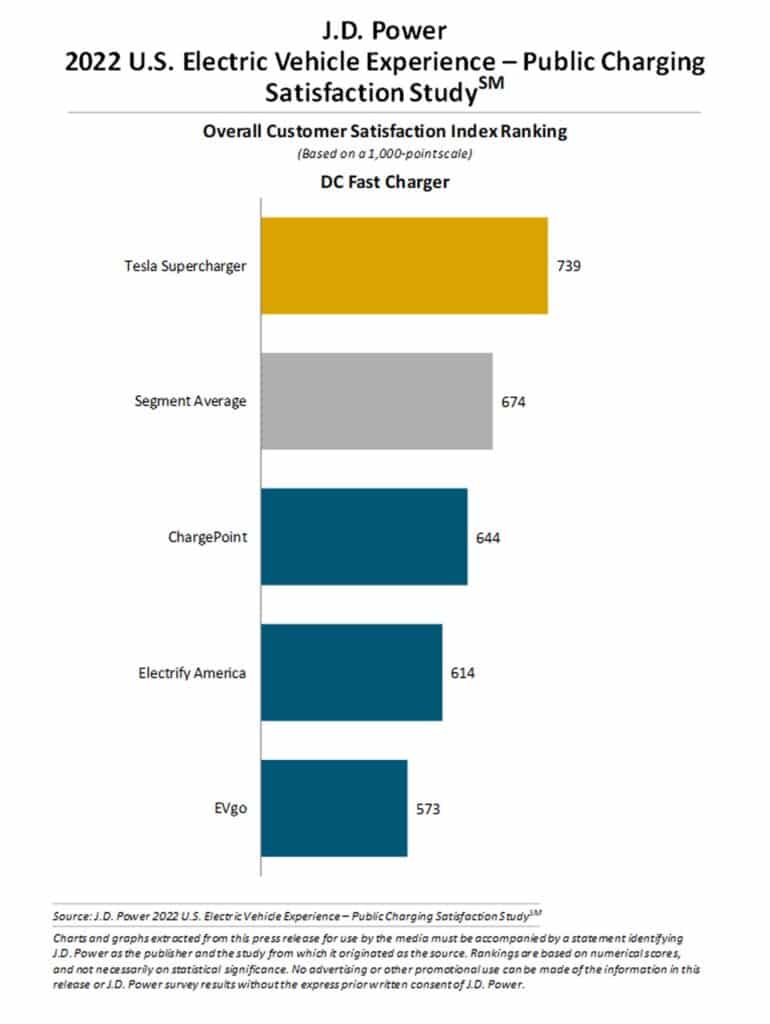

Where “range anxiety” was long the biggest concern for potential EV buyers, “charger anxiety” is rapidly becoming the bigger concern. And in two ways. There’s the time it takes to power up. It can run an hour or more using public quick chargers on many of today’s EVs to go from a 10% to 80% state-of-charge. But some newer models are cutting that down to 20 minutes or less under optimum situations and that should become the norm.

Then there’s the question of where to charge? Right now, there are an estimated 250,000 publicly accessible chargers, the vast majority still using much slower 240-volt Level 2 technology. Prior to the release of the new Biden emissions target, about 2 million public chargers — with a much higher share of DC quick chargers — were seen needed to power up an estimated 38 million EVs on the road by 2030, according to S&P Global Mobility, Expect to see those numbers revised upwards now.

Currently, at least 80% of EV owners routinely charge at home or office — which means they start most days with a full tank of electrons. But what about the 44 million Americans living in apartments and at least 6 million more who won’t have a place to install a charger.

“If the infrastructure was available, I’d buy (an EV) tomorrow,” said Pat Rizzo, a researcher for an environmental organization in New York. “But it’s not there, yet, for urban dwellers,” added Rizzo, noting that he’s likely to go with a hybrid “until the infrastructure catches up.”

The new rules are expected to accelerate demand for companies like Dallas-based Amperage Capital which is working with medium to large apartment building owners to wire up their parking lots and structures. And many commercial parking operators, like Philadelphia’s Parkway Corp., are beginning to wire up their own facilities.

Ahead of passage of the Infrastructure and IRA bills, private charging companies were powering up hundreds of new sites weekly. That may need to be raised by an order of magnitude. Those bills have set aside billions to grease the wheels.

But there’s another issue: faulty chargers. One study, released by the University of California — Berkeley last year found nearly a third of the public chargers in the San Francisco Bay Area not functioning at any given time. “If EV owners continue to experience chargers that don’t work as well as expected, that’s going to slow the EV revolution down,” said auto analyst and AutoLine.tv host John McElroy.

Rebuilding the infrastructure

Those measures also are putting billions where it arguably is needed more. Officials with Michigan’s DTE and several other major utilities that spoke to TheDetroitBureau.com believe they can readily handle the anticipated growth of EV sales, at least through the middle of the next decade. The new rules may require them to rethink plans.

There is substantial new generating capacity going into place across the U.S., though that varies “from region to region, state to state and utility to utility,” cautioned Dave Reuter, chief marketing and communications officer for NextEra Energy, based in Jacksonville, Florida. Without pointing fingers, Reuter worries that some providers simply aren’t adapting to what is necessary going forward.

Gary Silberg, a partner and leader of KPMG’s global automotive sector is even less upbeat. “Even before you throw in electric vehicles, (the U.S. electric infrastructure) is going to need a lot of work.”

There are really three key parts to the electric grid: generation, transmission — those high-power lines and towers that crisscross the U.S. — and local distribution. All three have challenges, but the transmission and distribution grid may be the most worrisome because “it is very old, with a quarter of it over 50 years old,” said Christine Oumansour, a partner in consulting firm Oliver Wyman’s energy practice.

Collectively, energy companies are investing $100 billion annually to upgrade the grid. Experts agree that will have to go up —substantially.

Politics

President Joe Biden has made EVs a core tenet of his administration, the president dedicating billions of dollars — notably from the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act — to help promote their adoption.

We’re barely a year away from the next presidential election, however, and it’s far too soon to be sure whom the candidates will be, never mind which party will emerge victorious. What’s clear is that Democrats and Republicans have very different visions of the nation’s automotive future. If anything, former President Donald Trump rolled back emissions and mileage standards — a move Biden quickly reversed after assuming office, the proposed numbers arriving from the Environmental Protection Agency this week.

Not surprisingly, that Reuters/Ipsos poll found a wide chasm separating voters when it comes to purchasing an EV. As TheDetroitBureau.com reported earlier this week, “Democrats are twice as likely as Republicans to buy one: 50% versus 26%. However, independents sided with Republicans with just 27% eager to plug in their next car, truck or crossover.” That was echoed by this week’s Gallup poll. It found almost identical results based on declared party affiliation.

That kind of division, along with the party’s greater skepticism about climate change, could mean a rollback of the Biden emissions plan should the GOP retake the White House in 2024 — all the more so if Democrats lose the Senate and Republicans retain the House of Representatives.

But we might not have to wait until then for politics to play a role. A number of GOP-controlled states have already signaled plans to challenge the new rules in court. On the flip side, Democrats, could become even more emboldened should the courts, and voters, move in favor of EVs over the next two years, bowing to environmentally minded supporters who have called for even stricter rules and more aggressive federal spending.

Coming together

“Never the twain shall meet?” Perhaps the political divide will be bridged as more EVs in more segments come to market. Curiously, “our data tells us truck intenders are (among all potential buyers) the most interested in EVs,” Mike Koval Jr., the CEO of the Ram brand, said during the New York International Auto Show recently. Data also shows them to be some of the most politically conservative.

Ford has its own data backing Koval up. It quickly logged 200,000 advance reservations for the F-150 Lightning when the pickup was launched, far beyond the annual 25,000 production capacity it planned for.

On the whole, EV owners appear to be more satisfied with their vehicles than those with conventional vehicles — though concerns about charging are significant. How that will shake out in the coming decade is uncertain.

Time for a recount?

The Biden administration has set in motion a transition that is unlike any the auto industry has experienced in more than 100 years. During the first decade of the 20th Century, steam and electric vehicles were far more popular than those running on gasoline. It took developments like the electric starter, as well as the discovery of plentiful oil in Texas and Oklahoma for the internal combustion engine to emerge the winner.

Now, we’re about to see a recount. There are solid reasons to bet on EVs. But a lot has to fall into place to make this 21st Century revolution take hold.