In the annals of war and peace, neither go as expected.

As World War II comes to an end, Chevrolet General Manager M.E. Coyle remembers what happened after World War I, when a series of recessions nearly sank the company. It’s 1945, and the federal government announces that it’s lifting its ban on building new cars, enacted in 1942 so that carmakers could focus on producing armaments, not automobiles.

But this time, Coyle’s going to be prepared, as he fears a postwar recession.

In contrast, Alfred P. Sloan, GM’s chairman, believes the United States is about to experience unmatched prosperity due to pent-up demand from the Great Depression and the lack of new car production during World War II.

Yet in 1945, despite not believeing in the need for small, inexpensive cars, Sloan gives the go-ahead for work to proceed on the Chevrolet Light Car Project, much to the delight of Chevrolet’s chief engineer, Earle MacPherson. This is why, during this week in 1945, then-GM President Charles Wilson announces plans to build the Cadet, a small economy car that will sell for less than $1,000 for 1948. At the time, full-size Chevrolets start at $1,050.

Unbeknownst to Chevrolet, the project will lead to revolutionary engineering.

A dream assignment

The engineer that will guide Chevrolet’s new car, Earle MacPherson, is born in Highland Park, Illinois in 1891, joining the Chalmers Motor Co. in Detroit after graduating college in 1915. With the outbreak of World War I, he finds himself in Europe working on Army aircraft engines.

At war’s end, he begins a career at the Liberty Motor Car Co. in Detroit until it closes in 1923. He moves on to Hupp Motor Car Co., where he remains until management squabbles drive him to join General Motors in the central engineering office in 1934. He becomes chief design engineer for Chevrolet the following year.

A decade later, he lands the assignment that would immortalize his name.

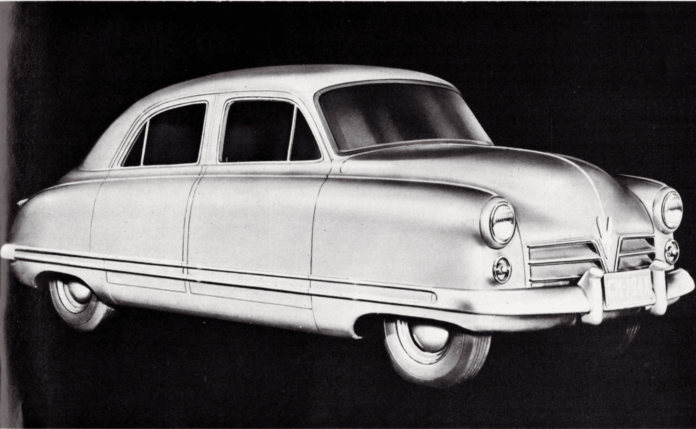

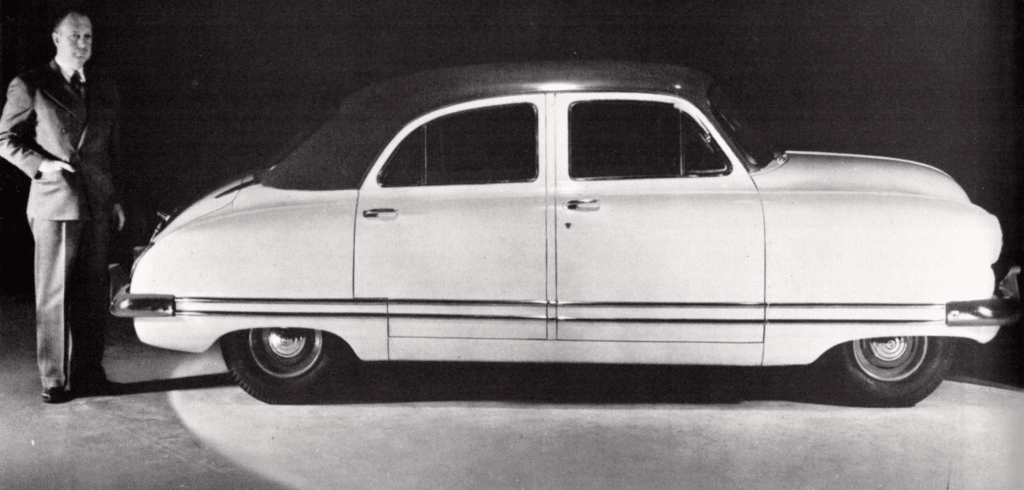

What results is dubbed the Cadet, a strikingly small compact sedan designed by Ned Nickels, who would go on to lead Buick design. Boasting a wheelbase of 108 inches, it’s far shorter than Chevrolet’s existing 116-inch wheelbase. It’s also a unibody design in an age of body-on-frame construction, and rides on Lilliputian 12-inch wheels hidden behind fender skirts at each corner.

Initially, MacPherson experiments with a number of driveline configurations: front-wheel drive, rear-mounted engine/rear-wheel drive, and conventional front engine/rear-wheel drive, which is ultimately what he would choose.

Power comes from a 65-horsepower 2.2-liter overhead-valve, inline 6-cylinder engine and connects to the 3-speed manual transmission under the front seat. MacPherson combines the engine, transmission and differential into a single assembly, similar to what would later be used in the 1961 Pontiac Tempest.

It weighs 2,200 pounds and holds four passengers.

Chevrolet’s innovation

But it’s the suspension that proves revolutionary.

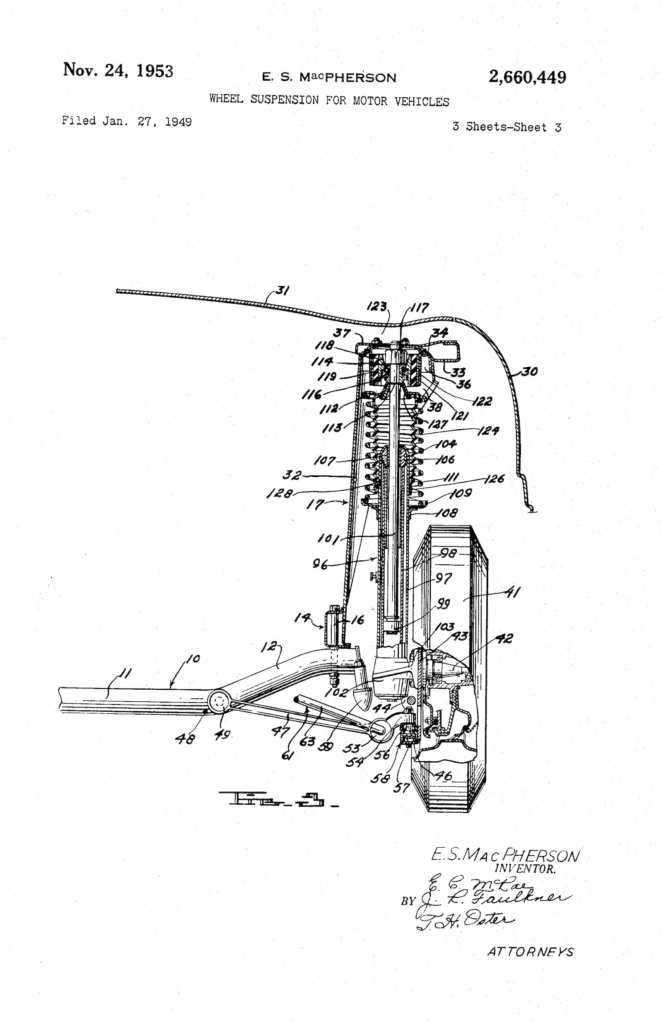

In an effort to provide more cabin and trunk space inside the diminutive automobile, MacPherson’s designs a vertical strut that’s used as the upper anchor point for the wheel hub and comprised of a tubular shock through the center of a coil spring. Each wheel is independently sprung, with radius rods controlling the lower end of each strut. This was far different from the typical beam axle suspension of the period, which didn’t have nearly the wheel travel of this novel new design.

Not only does MacPherson’s compact design save space, its simplicity reduces the number of parts needed to build it, which results in it weighing less than conventional designs. GM testing reveals it to be startlingly sturdy, while providing remarkable handling. Testers find the car handles better than contemporary Cadillacs, with generous wheel travel and a light, sharp feel.

It becomes known as the MacPherson strut, a design universally used in automobiles today.

So, what happened?

In September 1946, even as factories are being outfitted to build the Cadet, Chevrolet announces Cadet production is being postponed due to a shortage of lead, copper, pig iron and flat rolled steel. Yet development continues, with the Cadet getting suspended brake and clutch pedals, a novel idea at the time but now universally used.

But with the dawn of 1947, the Cadet’s prospects dim as GM’s beancounters conclude that Chevrolet would have to build 300,000 annually to make any kind of return on the car if it’s price was less than $1,000.

By May, GM’s Engineering Policy Group gathers to decide the Cadet’s fate. In the interim, the booming economy has GM selling every conventional Chevrolet it can build. What Sloane predicted comes to pass.

The Cadet isn’t needed.

On May 15, 1947, exactly two years after the Cadet was first revealed, GM releases a statement. “The proposed Chevrolet lighter car project has been indefinitely deferred.” GM blames material shortages and overwhelming demand for its current line of cars for the postponement.

Nevertheless, development continues as GM keeps MacPherson occupied until they can reassign him within GM. But MacPherson doesn’t wait around. He jumps to Ford Motor Company at the urging of Director of Engineering Harold T. Youngren in September 1947. Two years later, MacPherson applies for a patent on his suspension design. In the meantime, he is named Ford’s chief engineer in 1952, before his patent is granted the following year. He retires in May 1958, dying in his sleep in 1960 at the age of 69. Eight years later, GM scraps the last Cadet prototype.

A lasting legacy

As it turns out, the Cadet proves influential as other automakers market compacts in the wake of GM’s attempt, including the 1950 Nash Rambler, 1951 Kaiser Henry J and 1953 Hudson Jet. Of these, only the Nash proves successful. It will be another decade before Americans begin to appreciate the value of thinking small.

But it’s the Cadet’s suspension that would earn MacPherson lasting fame, as its design requires unibody construction. That’s because the top of the strut must secure to the chassis to support the suspension forces; the strut can’t be mounted to a body-on-frame vehicle body. Because modern cars are almost universally unibody, with tall overhead camshaft engines, the MacPherson strut is now common.

It was an engineering innovation GM let slip through its fingers.

Ironically, it would take another 33 years before the MacPherson strut is employed by GM on the 1980 Chevrolet Citation, Pontiac Phoenix, Oldsmobile Omega and Buick Skylark.

Thankfully, GM didn’t let the same thing happen with the GM Autonomy, the skateboard chassis it created and patented in 2001, and is now used by every EV manufacturer.