Everything was going so well until it wasn’t. It was October 1929, when the Roaring ’20s hit the wall — as did Studebaker’s plans to challenge General Motors, a strategy that was formalized this week in 1928. When the plans go awry, it doomed one of America’s great luxury automakers.

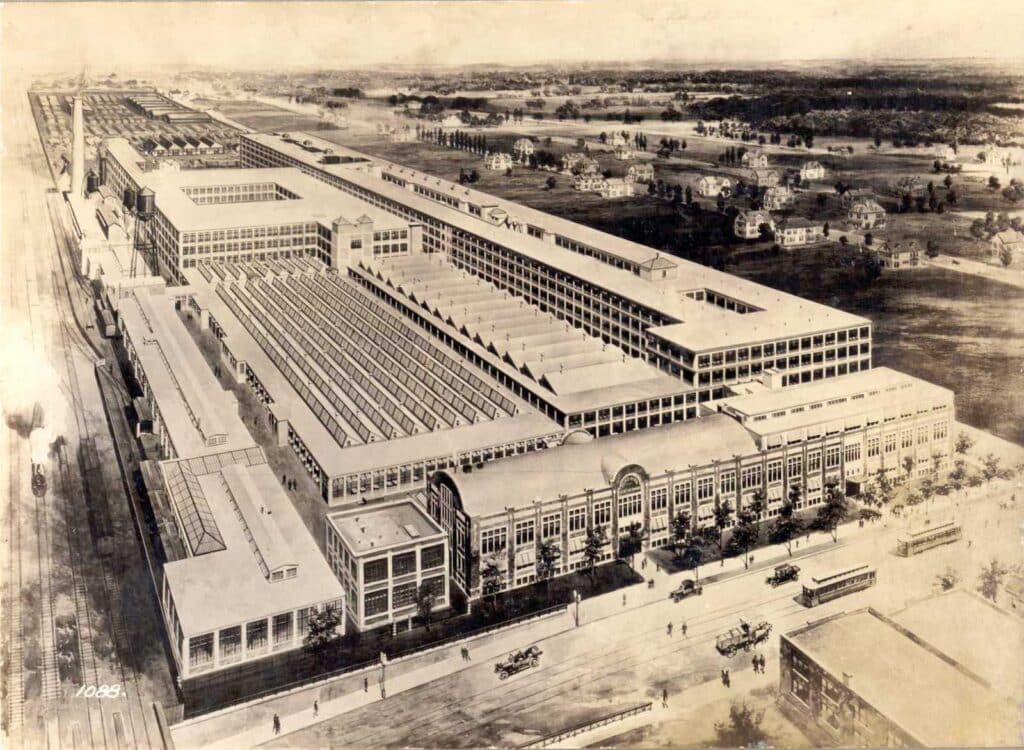

But it wasn’t so gloomy when George N. Pierce founded his eponymous company in 1867 in Buffalo, New York, producing household goods such as birdcages and iceboxes. As the 1870s dawned, he began manufacturing bicycles until the allure of the automobile proved to be too much.

In 1901, the company introduces its first car, the single-cylinder, 600-pound Pierce Motorette, three years before Studebaker, then the world’s largest wagon manufacturer. But the companies couldn’t have been more different.

The commoner from Indiana

Studebaker, of South Bend, Indiana, entered the automobile business building its own battery-electric vehicles through 1911, when it switched solely to gasoline-powered vehicles for the medium-priced market.

Pierce couldn’t be more different.

By 1905, the company introduces the Great Arrow, powered by a 5.0-liter T-head inline four-cylinder engine and single carburetor producing 32 horsepower through a 3-speed manual transmission. It goes on to win the first $2,000 Glidden Trophy at the 1905 AAA Reliability Tour, an honor the company holds for five consecutive years. Its cars continue to grow in size and prestige, as the company is renamed the Pierce-Arrow Motorcar Co., its hood mascot a kneeling archer with his bow drawn and ready to shoot.

It quickly becomes one of America’s premiere luxury car manufacturers, referred to as one of the “Three Ps” alongside competitors Packard and Peerless. Its reputation is solidified in 1909, when President Howard Taft orders two for the first official White House automotive fleet. His successor, President Woodrow Wilson, was greeted by a Pierce-Arrow limousine when he returned from negotiating the Treaty of Versailles in Paris in 1919. Friends bought it from the government as a present for him once he left office.

These were large cars with large price tags. Consider the 1912 Pierce-Arrow Model 66, with a 147-inch wheelbase chassis, tires four feet high and a 13.5-liter T-head 6-cylinder engine that was rated at 66 hp at a time when Ford Model T’s 2.9-liter inline 4-cylinder produced 20 hp. And the Model 66 would set you back $8,000; that’s $248,267 adjusted for inflation.

Styling is fairly conservative upright and formal, something that didn’t change, even as the America entered the Jazz Age, but one that’s appropriate for its old-money clientele. In fact, the company’s cars were all right-hand drive until 1920 — a sign of its conservative engineering.

Studebaker was enjoying a fair amount of success as well. The company built its last wagon in 1919, faring well in the 1920s.

The urge to merge

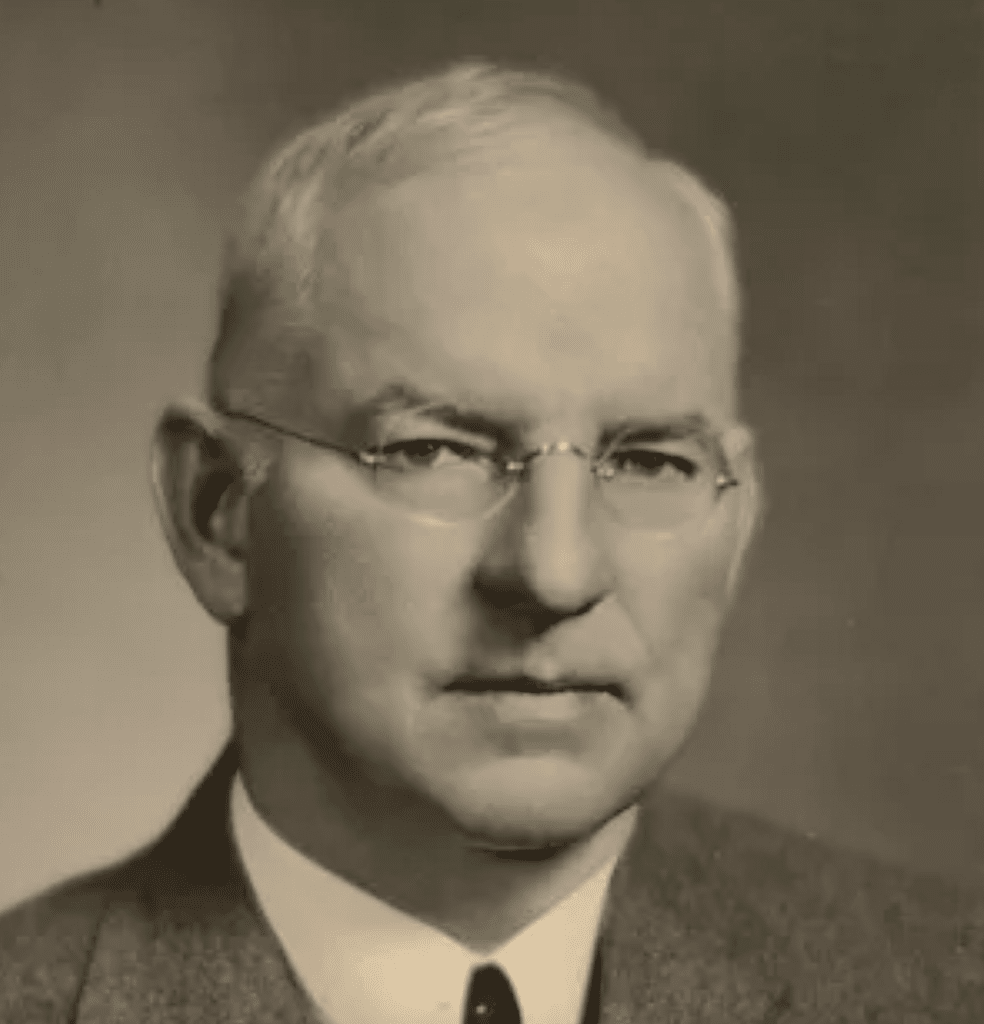

But Studebaker President Albert Erskine sets his sights on becoming a full-line manufacturer, a la General Motors. With the Erskine at the low end and Studebaker in the mid-price segment, the company only lacked a luxury car brand. The company became interested in acquiring an automotive blue blood, Pierce-Arrow.

At the time, Pierce-Arrow was offering two vehicles, the lower-priced Type 80, starting at $3,000, and the Type 33, starting at $5,200. But Pierce-Arrow Motor Car Co. President Myron E. Forbes felt that the days of the independent automaker were coming to an end — an apt prediction. The urge for automakers to merge came after Chrysler Corp. completed its acquisition of Dodge Brothers, according to contemporary reports from The New York Times.

It was known that Nash Motors of Kenosha, Wisconsin, was in merger discussions, according to a Time Magazine report in 1928. But President Charles Nash remained tight-lipped.

And, it was also known that Jordan Motor Car Co. President Edward Jordan of Cleveland considered a merger with Pierce-Arrow. Yet conversations didn’t get far, as both companies denied they were talking despite published rumors to the contrary.

So, this week in 1928, Forbes initiated informal talks with Studebaker’s Erskine, which had a thriving $135.9 million business at the time. By contrast, 450 miles away in Buffalo, N.Y., things weren’t nearly as flush, as Pierce-Arrow’s assets amounted to a mere $24.4 million. While the company served a conservative clientele, its equally conservative technology and design didn’t keep pace with the industry, and its products started to lag its competitors.

But Pierce-Arrow’s name and reputation still resonated, and Erskine wanted Studebaker to challenge General Motors’ Cadillac and Ford Motor Co.’s Lincoln. Pierce-Arrow seems like the perfect fit. And initially, it is.

A successful merger — at first

Under Studebaker’s ownership, Pierce-Arrow is able to update its stodgy product lineup, with cars that are faster, handle better, and have a lower profile. They also cost less, leading to the company’s best sales year ever, selling more than 8,000 units. The company plans for more of the same in 1930.

But no one had counted on the Great Depression.

Still, Pierce-Arrow’s customers still have money to spend, despite billions of dollars of wealth evaporating overnight. In fact, 1930 is the company’s second-best sales year ever with a volume of 7,670 cars. But rather than remaining cautious, Studebaker executives naturally feel that Pierce-Arrow is somehow immune to the vagaries of the Great Depression, and expand the brand’s line-up for 1931.

Sales crater, coming in at a mere 3,775 units. Annual industry-wide sales barely break a million units, down from more than 4 million in 1929. Even those who had money aren’t splurging.

But rather than retrench and conserve resources, the company fields a new 150-hp, 7.0-liter V-12 for 1932. And prices are far lower than they once were, starting at $4,295. Yet sales continue to decline, as the country heads into the bowels of the Great Depression, coming in at a scant 2,692 units for the year, causing Pierce-Arrow to post a $3-million loss on sales of $8 million.

Bad times

By then, Pierce-Arrow’s parent company is in trouble as well.

Studebaker’s sales had collapsed with the onset of the Great Depression, much like the rest of the industry, inducing huge losses, worker layoffs and wage cuts. Erskine’s plans are imploding.

His self-named entry-level model introduced for 1929 is dropped in 1930. It’s replaced by the Rockne, named for Notre Dame University’s football coach Knute Rockne. But it’s 1932, and most car buyers are not Notre Dame football fans. The car lasts through 1933, but it does little to help the bottom line, as sales of all cars remain meager. Even worse, Erskine equipped two plants in Detroit to build the car, straining company finances. But even as Studebaker’s financial health deteriorates, the company inexplicably continues to pay generous dividends.

Cash runs out.

On March 18, 1933, Studebaker enters receivership. Erskine is forced out of the company, later committing suicide on July 1, 1933. New managers are brought in, and they order Pierce-Arrow sold to a group of Buffalo businessmen and bankers for $1 million.

But the market they face is a daunting one. While Packard, Cadillac and Lincoln survive, Peerless and Marmon are gone. Studebaker would reorganize by 1935 and continue until exiting the car business in 1966.

For Pierce-Arrow, it is the beginning of the end.

Company executives knew that they could remain viable with sales of 3,000 units a year. To ensure this, the company introduces the stunningly advanced 1933 Pierce-Arrow Silver Arrow alongside restyled mainstream models. It works, at least for the first quarter of 1933. Despite new models arriving for 1934 and 1935, sales continued to slide, never reaching a breakeven point, let alone profitability. The company remains active until 1937, selling 166 units for the year, and manage to build 17 1938 models.

But time and cash run out, and the company files for bankruptcy by the end of the year, and is liquidated in May 1938, whose cars are now cherished classic collectible cars.